Birds have long been our inspiration for flight, and researchers at Princeton University have found a new trick in their arsenal: covert feathers. These small feathers on top of birds’ wings lay flat during normal flight but flare up in turbulence during landing. By attaching flexible plastic strips – “covert flaps” – to the top of a wing, the team has demonstrated impressive gains in aircraft performance at low speeds.

Wind tunnel tests and RC aircraft trials revealed a fascinating two-part mechanism. The front flaps interact with the turbulent shear layer, keeping it close to the wing surface, while the rear flap create a “pressure dam” that prevents high-pressure air from moving forward. The result? Up to 15% increase in lift and 13% reduction in drag at low speeds. Unfortunately the main body of the paper is behind a paywall, but video and abstract is still fascinating.

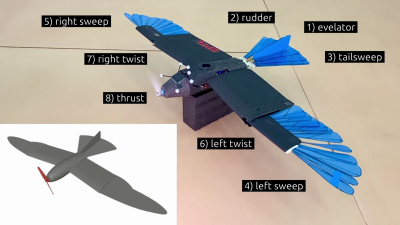

This innovation could be particularly valuable during takeoff and landing – phases where even a brief stall could spell disaster. The concept shares similarities with leading-edge slats found on STOL aircraft and fighter jets, which help maintain control at high angles of attack. Imitating feathers on aircraft wings can have some interesting applications, like improving control redundancy and efficiency.

Continue reading “Small Feathers, Big Effects: Reducing Stall Speeds With Strips Of Plastic”