If someone sent you an advert for an electric car with a price too low to pass up, what would you do? [Leadacid44] was in that lucky situation, and since it was crazy cheap, bought the car.

Of course, there’s always a problem of some kind with any cheap car, and this one was no exception. In this case, making it ‘go’ for any reasonable distance was the problem. Eventually a faulty battery charging system was diagnosed and fixed, but not before chasing down a few other possibilities. While the eventual solution was a relatively simple one the write-up of the car and the process of finding it makes for an interesting read.

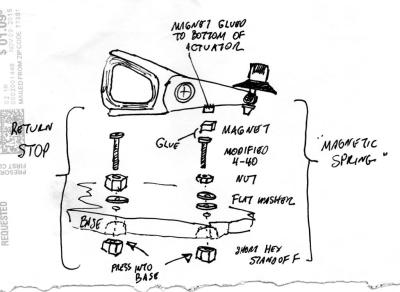

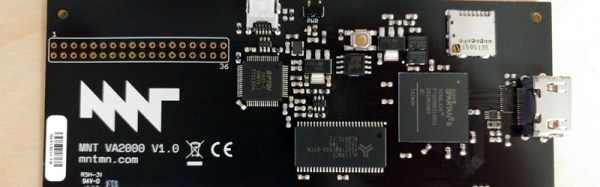

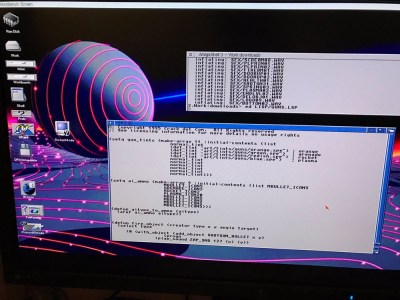

The car in question is a ZENN, a Canadian-made and electric-powered licensed version of the French Microcar MC2 low-speed city car with a 72 volt lead-acid battery pack that gives a range of about 40 miles and a limited top speed of 25 miles per hour. Not a vehicle that is an uncommon sight in European cities, but very rare indeed in North America. Through the write-up we are introduced to this unusual vehicle, the choice of battery packs, and to the charger that turned out to be defective. We’re then shown the common fault with these units, a familiar dry joint issue from poor quality lead-free solder, and taken through the repair.

We are so used to lithium-ion batteries in electric cars that it’s easy to forget there is still a small niche for lead-acid in transportation. Short-range vehicles like this one or many of the current crop of electric UTVs can do without the capacity and weight savings, and reap the benefit of the older technology being significantly cheaper. It would however be fascinating to see what the ZENN could achieve with a lithium-ion pack and the removal of that speed limiter.

If your curiosity is whetted by European electric microcars, take a look at our previous feature n the futuristic Hotzenblitz, from Germany.