Most of us associate the name Sega with their iconic console gaming systems from the 1980s and 1990s, and those of us who maintain an interest in arcade games will be familiar with their many cabinet-based commercial offerings. But the company’s history in its various entities stretches back as far as the 1950s in the world of slot machines and eventually electromechanical arcade games. [Arcade Archive] is starting to tell the take of how one of those games is being restored, it’s a mid-1960s version of Gun Fight, at the Retro Collective museum in Stroud, UK.

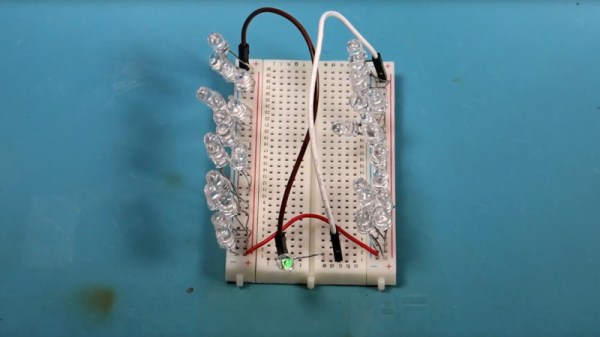

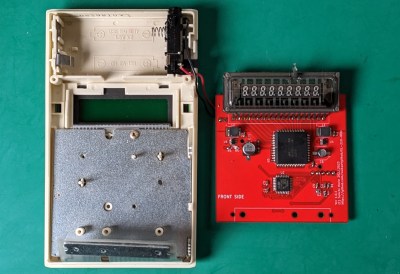

The game is a table-style end-to-end machine, with the two players facing each other with a pair of diminutive cowboys over a game field composed of Wild West scenery. The whole thing is very dirty indeed, so a substantial part of the video is devoted to their carefully dismantling and cleaning the various parts.

This is the first video in what will become a series, but it still gives a significant look into the electromechanical underpinnings of the machine. It’s beautifully designed and made, with all parts carefully labelled and laid out with color-coded wiring for easy servicing. For those of us who grew up with electronic versions of Sega Gun Fight, it’s a fascinating glimpse of a previous generation of gaming, which we’re looking forward to seeing more of.

This is a faithful restoration of an important Sega game, but it’s not the first time we’ve featured old Sega arcade hardware.

Continue reading “If You Thought Sega Only Made Electronic Games, Think Again”