As curious people, we’re all incredibly fortunate to live in an age where information can so easily be obtained. If you want to learn how something works, from a cotton gin to an RBMK reactor, you’re just a few keystrokes away from articles, diagrams, and videos on the subject. But as helpful as all of that information can be, we also know that there’s no substitute for hands-on experience.

While we can’t recommend you try building a miniature graphite-moderated nuclear reactor, there’s plenty of other devices that you can study by constructing your own functioning model. For example, when [Jorisclayton] wanted to really know what was going on inside a computer, they decided to go back to basics and build their own Z80 machine. To maximize the experience, they skipped any of the existing kit designs and instead wired the whole thing up by hand across a few perfboards.

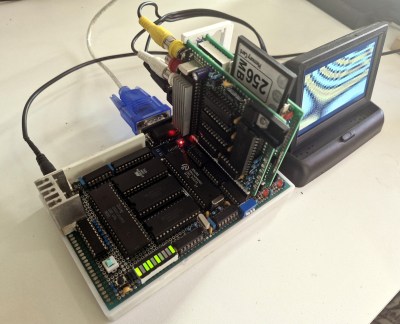

The main board contains a 4 MHz Z80 processor, paired with 32K ROM and 64K RAM. Here you’ll also find the clock generator, I/O decoder, serial port, voltage regulator, and a trio of expansion slots that use a long strip of 2.54 mm pin headers as the interface. In the first expansion slot you’ve got a primordial “graphics card” based around the TMS9918 video display controller (VDC) and 16K of additional RAM. The second expansion card has a CompactFlash reader and an LED array mapped to I/O address 0x00h so it can be used for various notifications.

The main board contains a 4 MHz Z80 processor, paired with 32K ROM and 64K RAM. Here you’ll also find the clock generator, I/O decoder, serial port, voltage regulator, and a trio of expansion slots that use a long strip of 2.54 mm pin headers as the interface. In the first expansion slot you’ve got a primordial “graphics card” based around the TMS9918 video display controller (VDC) and 16K of additional RAM. The second expansion card has a CompactFlash reader and an LED array mapped to I/O address 0x00h so it can be used for various notifications.

[Jorisclayton] says the final expansion board is still being worked on, but the idea is for it to handle user input through a PS/2 keyboard connector, as well as provide ports for a pair of Super Nintendo (or compatible) controllers. Everything is held together with a minimalist 3D printed frame to show off all that careful soldering.

Obviously there’s no PCB design files to share for this one, but [Jorisclayton] has posted a schematic for wiring everything up if you’re looking for resources to build your own Z80 computer. Sure the chips themselves might no longer be in production, but that doesn’t mean this venerable CPU is going anywhere just yet.