Off the hop, we love portable consoles. To be clear, we don’t just mean handhelds like the 3DS, or RetroPie builds, but when a maker takes a home console from generations past and hacks a childhood fantasy into reality — that’s amore. So, it’s only natural that [Bill Paxton]’s GameCube re-imagined as a Game Boy Advance SP has us enthralled.

Originally inspired by an early 2000’s imagined mockup of a ‘next-gen’ Game Boy Advance, [Paxton] first tried to wedge a Wii disk drive into this build. Finding it a bit too unwieldy, he opted for running games off of SD cards using a WASP Fusion board instead. Integrating the controller buttons into the 3D printed case took several revisions. Looking at the precise modeling needed to include the L and R shoulder buttons, that is no small feat.

Sadly, this GameCube SP doesn’t have an on-board battery, so you can’t go walking about with Windwaker. It does, however, include a 15 pin mini-din VGA-style port to copy game saves to the internal memory card, a switching headphone jack, amp, and speakers. Check it out after the break!

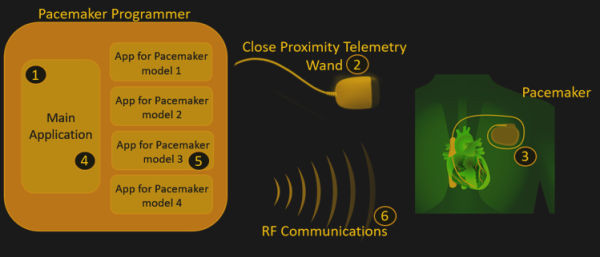

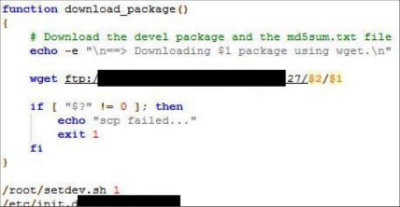

The programmers’ firmware update procedures were also flawed, with hard-coded credentials being very common. This allows an attacker to setup their own authentication server and upload their own firmware to the home monitoring kit. Due to the nature of the hack, the researchers are not disclosing to the public which manufacturers or devices are at fault and have redacted some information until these medical device companies can get their house in order and fix these problems.

The programmers’ firmware update procedures were also flawed, with hard-coded credentials being very common. This allows an attacker to setup their own authentication server and upload their own firmware to the home monitoring kit. Due to the nature of the hack, the researchers are not disclosing to the public which manufacturers or devices are at fault and have redacted some information until these medical device companies can get their house in order and fix these problems.