The Open Source Underwater Glider has just been named the Grand Prize winner of the 2017 Hackaday Prize. As the top winner of the Hackaday Prize, the Open Source Underwater Glider will receive $50,000 USD completes the awarding of more than $250,000 in cash prizes during the last eight months of the Hackaday Prize.

More than one thousand entries answered the call to Build Something That Matters during the 2017 Hackaday Prize. Hardware creators around the globe competed in five challenges during the entry rounds: Build Your Concept, Internet of Useful Things, Wings-Wheels-an-Walkers, Assistive Technologies, and Anything Goes. Below you will find the top five finisher, and the winner of the Best Product award of $30,000.

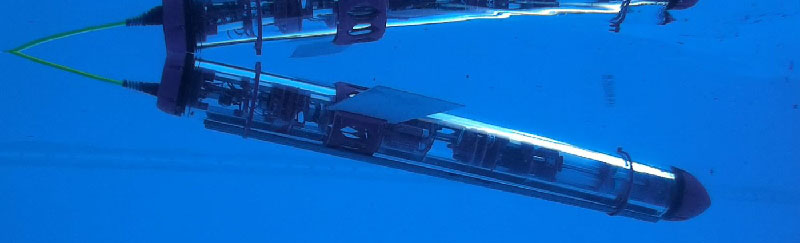

Open Source Underwater Glider

Grand Prize Winner ($50,000 USD): The Open Source Underwater Glider is an AUV (Autonomous Underwater Vehicle) capable of long-term underwater exploration of submarine environments. Where most AUVs are limited in both power and range, the Open Source Underwater Glider does not use active propulsion such as thrusters or propellers. This submersible glides, extending the range and capabilities of whatever task it is performing.

The Open Source Underwater Glider is built from off-the-shelf hardware, allowing anyone to build their own copy of this very capable underwater drone. Extended missions of up to a week are possible, after which the Glider would return home autonomously.

Connected Health: Open source IoT patient monitor

Assistance System for Vein Detection

Third Place ($15,000): This Assistance System for Vein Detection uses off-the-shelf components and near-IR imaging to detect veins under the skin. This system uses a Raspberry Pi and camera module or a modified webcam and yet is just as reliable as professional solutions that cost dozens of times more than this team’s prototype.

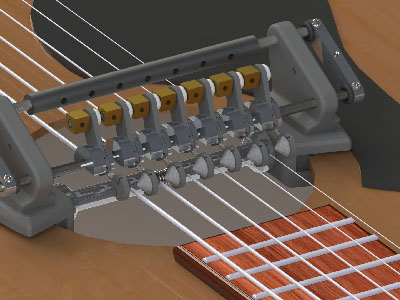

Adaptive Guitar

Tipo : Braille Smartphone Keypad

Best Product Winner: Tipo : Braille Smartphone Keypad

The winner of the Best Product is Tipo : Braille Smartphone Keypad. Tipo is the solution to the problem of the increasingly buttonless nature of modern smartphones. A phone that is only a touchscreen cannot be used by the visually impaired, and Tipo adds a Braille keypad to the back of any phone. It is effectively a USB keypad, designed for Braille input, that attaches to the back of any phone.

The Best Product competition ran concurrently with the five challenge rounds and asked entrants to go beyond prototype to envision the user’s needs, manufacturing, and all that goes into getting to market. By winning the Best Product competition, the creators of Tipo will refine their design, improve their mechanical build, start looking at injecton molding, and turn their 3D printed prototype into a real product that has the ability to change lives.

Congratulations to all who entered the Hackaday Prize. Taking time to apply your skill and experience to making the world better is a noble pursuit. It doesn’t end with the awarding of a prize. We have the ability to change lives by supporting one another, improving on great ideas, and sharing the calling to Build Something that Matters.

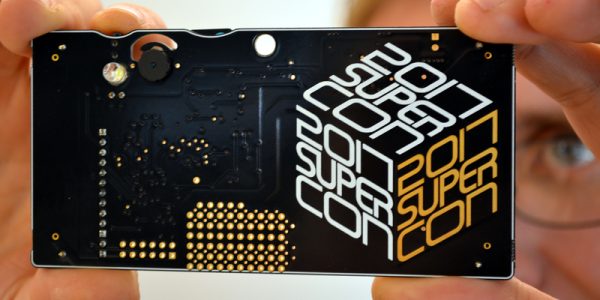

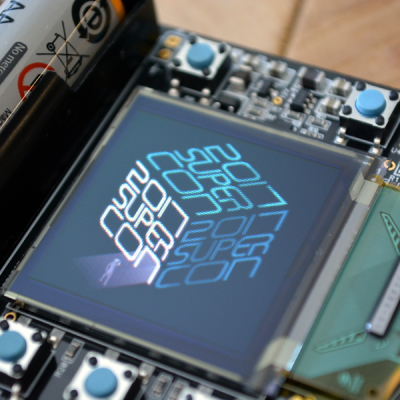

The Superconference is this weekend, and a few hundred Hackaday hackers will get their hands on this lump of open hardware. Something fantastic is certainly going to happen. If you couldn’t make it but still want to play along, now’s your chance!

The Superconference is this weekend, and a few hundred Hackaday hackers will get their hands on this lump of open hardware. Something fantastic is certainly going to happen. If you couldn’t make it but still want to play along, now’s your chance!