PC gaming in the modern era has become a GPU measuring contest, but back when computers had far fewer resources, every sprite had to be accounted for. To many, this was peak gaming. So let’s look to the greats of [Martin Hollis, David Moore, and Olly Betts], who had the genius (or insanity) to create Tetris in a single BBC BASIC line.

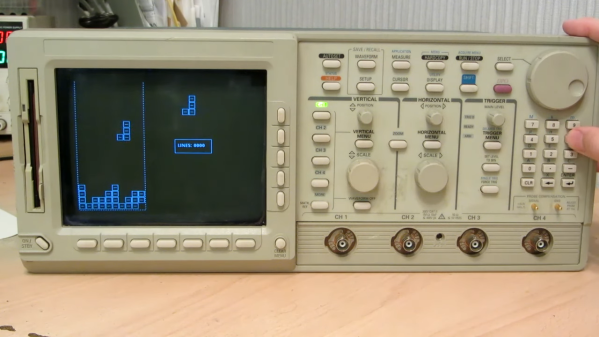

Created in 1992, one-line Tetris serves as a great use of the limited resources available. The entirety of the game fits within 257 bytes. With the age of BASIC, the original intent of the game for BBC BASIC was to be played on computers similar to Acorn’s BBC microcomputer or Archimedes.

One line Tetris has all the core features of the original game. Moving left, right, and rotating all function like the traditional game, most of the time. Being created in a single line, there were a few corners cut with bug fixing. Bugs such as crashing every 136 years of play due to large numbers or holding all keys causing the tetrominoes to freeze make it an interesting play experience. However, as long as our GPUs are long enough to play, we don’t mind.

If you want to experience the most densely coded gaming experience possible but don’t have one of the BBC BASIC computers of old, make sure to try this emulator with a copy of the game. Considering the amount done in a single line of BBC BASIC, the thought may come into mind on what could be done with MORE than a SINGLE line of code. For those with this thought, check out the capabilities of the coding language with modern hardware.

Thanks to [Keith Olson] for the tip!