Tiny Linux computers are everywhere, and between BeagleBones, Raspberry and Banana Pis, and a hundred other boards out there, there are enough choices to go around. There is an extremely interesting ARM chip from Xilinx that hasn’t seen much uptake in the field of tiny credit-card sized computers: the Zynq. It’s an ARM Cortex-A9 coupled with an FPGA. It’s great for building peripherals that wouldn’t normally be included on a microcontroller. With Zynq, you just instantiate the custom bits in the FPGA, then interface them with a custom Linux driver. Thanks to CrowdSupply, there’s now a board out there that brings this intriguing chip to a proper development platform. It’s called the Snickerdoodle, and if you’ve ever wanted to see the capabilities of an FPGA tightly coupled to a fast processor, this is the board to watch.

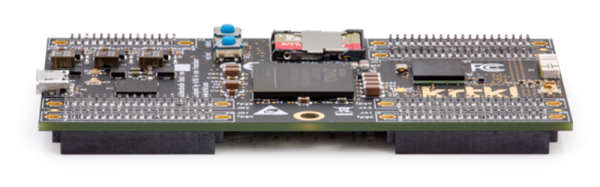

The core of the Snickerdoodle is a Xilinx Zynq that features either a 667 MHz ARM Cortex A9 and a 430k gate FPGA (in the low-end configuration) or an 866 A9 and 1.3M gate FPGA. This gives the Snickerdoodle up to 179 I/O ports – far more than any other tiny Linux board out there.

Fully loaded, the Snickerdoodle comes with 2.4 and 5GHz WiFi, Bluetooth, 1GB of RAM, and an ARM Cortex A9 that should far surpass the BeagleBone and Raspberry Pi 2 in capabilities. This comes at a price, though: the top-shelf Snickerdoodle has a base price of about $150.

Still, the power of a fast ARM and a big FPGA is a big draw and we’re expecting a few more of these Zynq boards in the future. There are even a few projects using the Zynq on hackaday.io, including one that puts the Zynq in a Raspberry Pi-compatible footprint. That’s exceedingly cool, and we can’t wait to see what people will build with a small, fast ARM board coupled to an FPGA.