Meet [Daniel Öster]. [Daniel] is a self-professed petrolhead. In other words, he’s a hot rodder who can’t leave well enough alone. Just because he’s driving a 2012 Nissan Leaf doesn’t mean he isn’t looking for a bit more kick. Having already upgraded the battery, [Daniel] turned his attention to upgrading the 80KW inverter. Not only was [Daniel] successful, but the work has been documented and the Open Source code made available on GitHub. Part of [Daniel]’s mission is to open up otherwise closed ecosystems and make EV hacking and repair approachable by mere mortals.

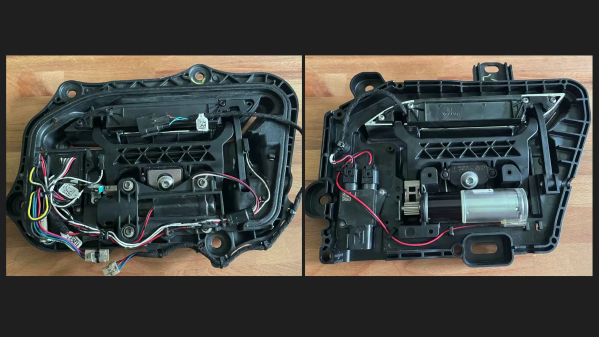

To get an extra 50hp, [Daniel] could have just swapped in the 110KW drivetrain from a 2018 or newer Leaf, but a less expensive route of swapping in only the 110KW inverter was chosen. By changing out just the inverter, the modification becomes more affordable for others to do. [Daniel] expertly documents how the new 110KW inverter has to be matched to the existing motor by setting a resolver correction value in the inverter.

Cutting into the wiring harness of a vehicle that one is still making payments on is an exercise reserved for only the most dedicated modders, but a change in connectors between 2012 and 2018 made it necessary. The only tools needed were wire cutters, a soldering iron, heat shrink, and perhaps some liquid courage.

Although the hack was successful, no performance gains were had initially, because the CAN bus signal going to the inverter never told it to provide more than the original 80KW. A CAN bus Man In The Middle attack was done by adding a CAN bridge device that listens to traffic on the CAN bus and bends it to [Daniel]’s will. By multiplying the KW signal by 1.3, the 80KW signal becomes 110KW, and full Ludicrous Speed is achieved! Excellent gains in 0-100kph times are seen, but [Daniel] isn’t done. His next hack will be to put in a 160KW inverter for even more go-pedal madness.

Be sure to watch the introduction video below the break. You might also be interested in Nissan Leaf hacks we’ve featured previously such as retrofitting a fast charging port, salvaging batteries from wrecks, and partly resolving serious charging flaws.

Continue reading “Open Source Hot Rod Mod Gives More Power To EV Owners”