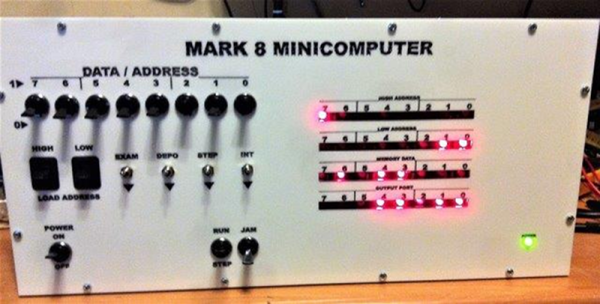

In the mid-1970’s there were several U.S.-based hobby electronics magazines, including Popular Electronics and Radio Electronics. Most people know that in 1975, Popular Electronics ran articles about the Altair 8800 and launched the personal computer industry. But they weren’t the first. That honor goes to Radio Electronics, that ran articles about the Mark 8 — based on the Intel 8008 — in 1974. There are a few reasons, the Altair did better in the marketplace. The Mark 8 wasn’t actually a kit. You could buy the PC boards, but you had to get the rest of the parts yourself. You also had to buy the plans. There wasn’t enough information in the articles to duplicate the build and — according to people who tried, maybe not enough information even in the plans.

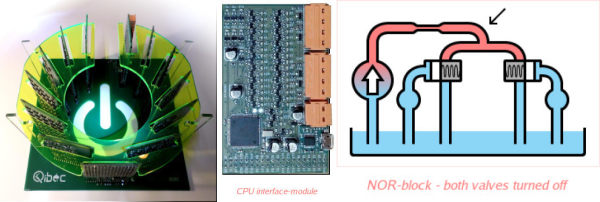

[Henk Verbeek] wanted his own Mark 8 so he set about building one. Of course, coming up with an 8008 and some of the other chips these days is quite a challenge (and not cheap). He developed his own PCBs (and has some extra if anyone is looking to duplicate his accomplishment). There’s also a video, you can watch below.