If you are a regular follower of these pages as well as a radio amateur, you may well have heard of [Ashhar Farhan, VU2ESE]. He is the designer of the BitX, a simple single-sideband transceiver that could be built for a very small outlay taking many of its components from a well-stocked junk box.

In the years since the BitX’s debut there have been many enhancements and refinements to the original, and it has become something of a standard. But it’s always been a single-band rig, never competing with expensive commercial boxes that cover the whole of the available allocations.

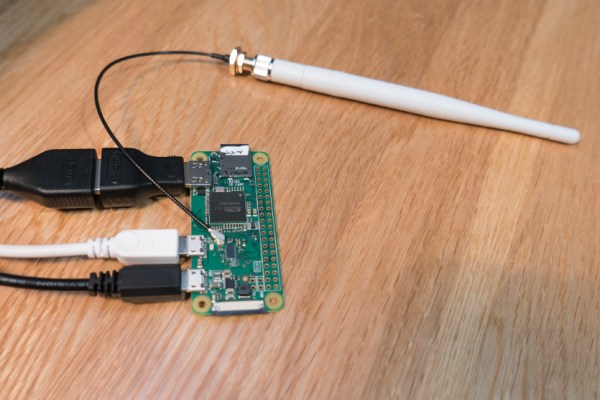

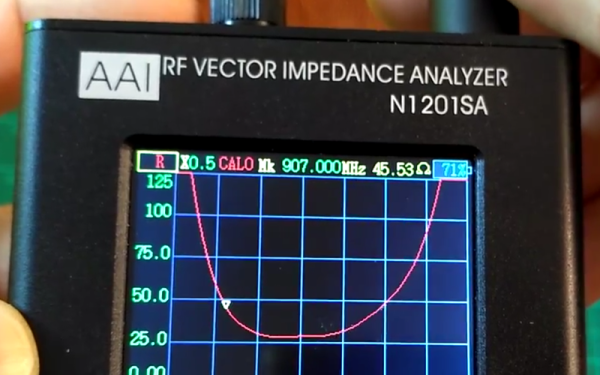

With his latest design, he’s changed all that. The uBITX (Micro-BITX when spoken aloud), is an SSB and CW transceiver that covers all of the HF amateur bands, and like the original is designed for the home constructor on a budget. It shows its heritage in the use of bi-directional amplifiers, but diverges from the original with a 45 MHz first IF and an Arduino/SI5351 clock generator in the place of a VFO. It looks to be an excellent design in the spirit of the original, and we can’t wait to see them in the wild.

He’s put up a YouTube video which we’ve placed below the break. His write-up is extensive and fascinating, but it is his closing remarks which sum up the project and the reason why you should build one. We don’t often reproduce entire blocks of text, but this one says it so well:

As a fresh radio amateur in the 80s, one looked at the complex multiband radios of the day with awe. I remember seeing the Atlas 210x, the Icom 720 and Signal One radios in various friends’ shacks. It was entirely out of one’s realm to imagine building such a general coverage transceiver in the home lab.

Devices are now available readily across the globe through online stores, manufacturers are more forthcoming with their data. Most importantly, online communities like the EMRFD’s Yahoo group, the BITX20’s groups.io community etc have placed the tribal knowledge within the grasp of far flung builders like I am.

One knows that it was just a matter of breaking down everything into amplifiers, filters, mixers and oscillators, but that is just theory. The practice of bringing a radio to life is a perpetual ambition. The first signal that the sputters through ether, past your mess of wires into your ears and the first signal that leaps out into the space from your hand is stuff of subliminal beauty that is the rare preserve of the homebrewer alone.

At a recent eyeball meet, our friend [Dev(VU2DEV)] the famous homebrewer said “Now is the best time to be a homebrewer”. I couldn’t disagree.

If you build a uBITX, please share it with us!

Continue reading “[Ashhar Farhan]’s Done It Again!” →