The world’s militaries have always been at the forefront of communications technology. From trumpets and drums to signal flags and semaphores, anything that allows a military commander to relay orders to troops in the field quickly or call for reinforcements was quickly seized upon and optimized. So once radio was invented, it’s little wonder how quickly military commanders capitalized on it for field communications.

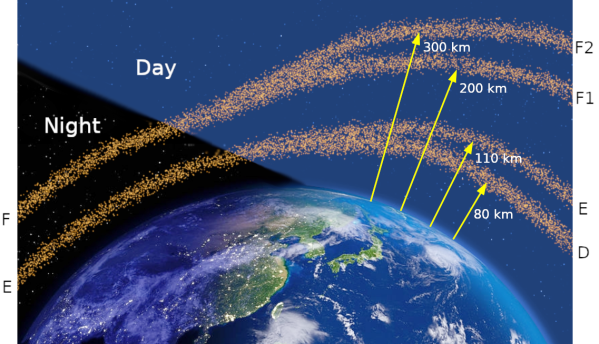

Radiotelegraph systems began showing up as early as the First World War, but World War II was the first real radio war, with every belligerent taking full advantage of the latest radio technology. Chief among these developments was the ability of signals in the high-frequency (HF) bands to reflect off the ionosphere and propagate around the world, an important capability when prosecuting a global war.

But not long after, in the less kinetic but equally dangerous Cold War period, military planners began to see the need to move more information around than HF radio could support while still being able to do it over the horizon. What they needed was the higher bandwidth of the higher frequencies, but to somehow bend the signals around the curvature of the Earth. What they came up with was a fascinating application of practical physics: meteor burst communications.

Continue reading “Radio Apocalypse: Meteor Burst Communications”