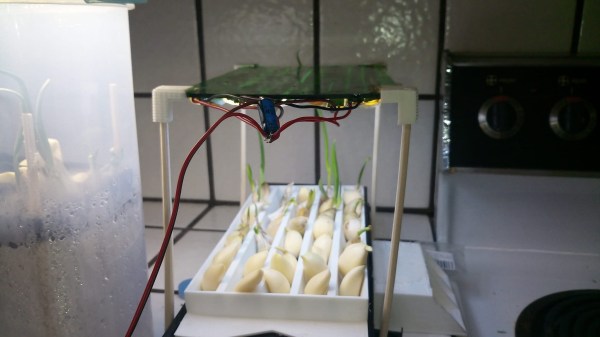

Certain pictures draw attention like no other, and that’s what happened when we stumbled upon a Twitter post about “resuscitating supermarket garlic” by [Robots Everywhere]. The more we looked at this photo, the more questions popped up, and we couldn’t resist contacting the author on Twitter – here’s what we’ve learned!

This is an aeroponics cell – a contraption that creates suitable conditions for a plant to grow. The difference of aeroponics, when compared to soil or hydroponics methods, is that the plant isn’t being submerged in soil or water. Instead, its roots are held in the air and sprayed with water mist, providing both plenty of water but also an excess of oxygen, as well as a low-resistance space for accelerated root growth – all of these factors that dramatically accelerate nutrient absorption and development of the plant. This cell design only takes up a tiny bit of space on the kitchen countertop, and, in a week’s time, at least half of the cloves have sprouted!

Much like a garlic bulb, this project has layers to it – in that this aeroponic cell is also a CellSol node! The CellSol project is a distributed communication system that can use LoRa and WiFi for its physical layer, enabling you to build widely spanning mesh networks that even lets you connect your smartphone to it where it’s called for – say, as an internet-connected hub for other devices to send their data through. We’ve covered CellSol and it’s hacker-friendliness previously, and one of the intentions of this design is to show how any device with a bit of brains and a SX1276 module can help you form a local CellSol network, or participate in some larger volunteer-driven CellSol-powered effort.

If, like us, you’re looking at this picture and thinking “this is something I’d love to see on my desk”, [Robots Everywhere] has published the STL files for making a hydroponic cell like this at home, as well as all the code involved, and some demo videos. Hopefully, the amount of aeroponics projects in our tips line is only going to increase! We’ve covered Project EDEN before, a Hackaday Prize 2017 entry that works to perfect an aeroponics approach to create an indoor greenhouse. There’s also a slew of hydroponics projects to have graced our pages, from hardware store-built to 3D printed ones!

Continue reading “Aeroponic Cell Grows Garlic, Forwards CellSol Packets” →