At this point in the tech dystopia cycle, it’s no surprise that the initial purchase price of a piece of technology is likely not the last payment you’ll make. Almost everything these days needs an ongoing subscription to do whatever you paid for it to do in the first place. It’s ridiculous, especially when all you want to do is charge your electric motorcycle with electricity you already pay for; why in the world would you need a subscription for that?

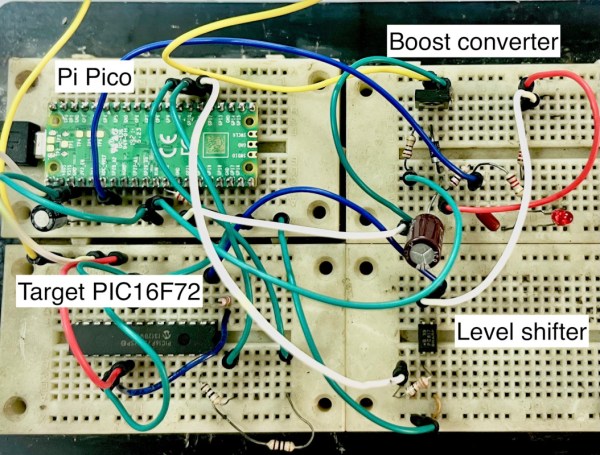

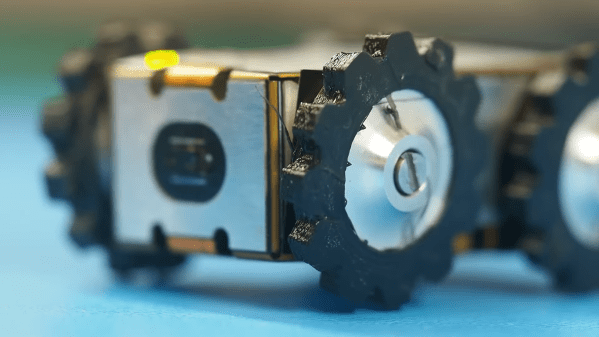

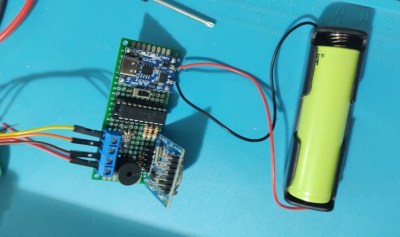

That was [Maarten]’s question when he picked up a used EVBox wall mount charger, which refused to charge his bike without signing up for a subscription. True, the subscription gave access to all kinds of gee-whiz features, none of which were necessary for the job of topping off the bike’s battery. A teardown revealed a well-built device with separate modules for mains supply and battery charging, plus a communications module with a cellular modem, obviously the bit that’s phoning home and keeping the charger from working without the subscription.

Continue reading “Fail Of The Week: Subscription EV Charger Becomes Standalone, Briefly”