Even if you are relatively young, you can probably think back on what TV was like when you were a kid and then realize that TV today is completely different. Most people watch on-demand. Saturday morning cartoons are gone, and high-definition digital signals are the norm. Many of those changes are a direct result of the Internet, which, of course, changed just about everything. Ham radio is no different. The ham radio of today has only a hazy resemblance to the ham radio of the past. I should know. I’ve been a ham for 47 years.

You know the meme about “what people think I do?” You could easily do that for ham radio operators. (Oh wait, of course, someone has done it.) The perception that hams are using antique equipment and talking about their health problems all day is a stereotype. There are many hams, and while some of them use old gear and some of them might be a little obsessed with their doctor visits, that’s true for any group. It turns out there is no “typical” ham, but modern tech, globalization, and the Internet have all changed the hobby no matter what part of it you enjoy.

Radios

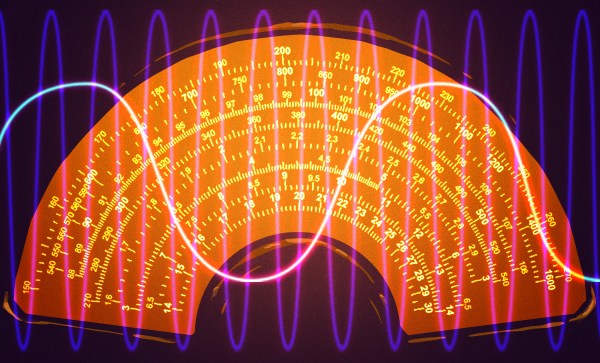

One of the biggest changes in the hobby has been in the radio end. Hams tend to use two kinds of gear: HF and VHF/UHF (that’s high frequency, very high frequency, and ultra-high frequency). HF gear is made to talk over long distances, while VHF/UHF gear is for talking around town. It used to be that a new radio was a luxury that many hams couldn’t afford. You made do with surplus gear or used equipment.

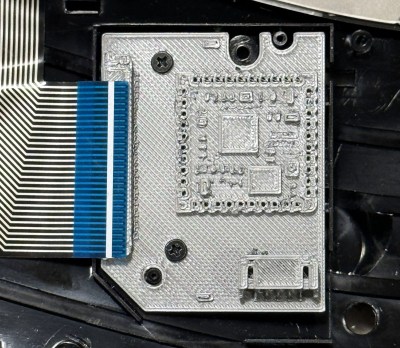

Globalization has made radios much less expensive, while technological advances have made them vastly more capable. It wasn’t long ago that a handy-talkie (what normal folks would call a walkie-talkie) would be a large purchase and not have many features. Import radios are now sophisticated, often using SDR technology, and so cheap that they are practically disposable. They are so cheap now that many hams have multiples that they issue to other hams during public service events.