We talk about ransomware gangs quite a bit, but there’s another shadowy, loose collection of actors in that arena. Emsisoft sheds a bit of light on the network of researchers and law enforcement that are working behind the scenes to frustrate ransomware campaigns.

Darkside is an interesting case study. This is the group that made worldwide headlines by hitting the Colonial Pipeline, shutting it down for six days. What you might not realize is that the Darkside ransomware software had a weakness in its encryption algorithms, from mid December 2020 through January 12, 2021. Interestingly, Bitdefender released a decryptor on January 11. I haven’t found confirmation, but the timing seems to indicate that the release of the decryptor triggered Darkside to look for and fix the flaw in their encryption. (Alternatively, it’s possible that it was released in response the fix, and time zones are skewing the dates.)

Emsisoft is very careful not to tip their hand when they’ve found a vulnerability in a ransomware. Instead, they have a network of law enforcement and security professionals that they share information with. This came in handy again when the Darkside group was spun back up, under the name BlackMatter.

Not long after the campaign was started again, a similar vulnerability was reintroduced in the encryption code. The ransomware’s hidden site, used for negotiating payment for decryption, seems to have had a vulnerability that Emsisoft was able to use to keep track of victims. Since they had a working decryptor, they were able to reach out directly, and provide victims with decryption tools.

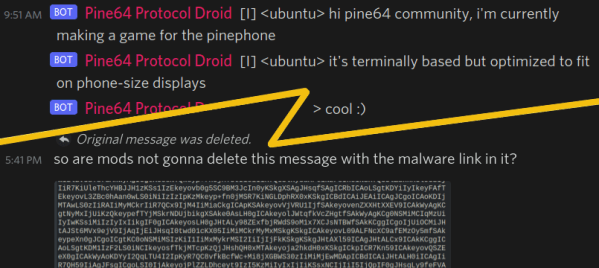

This changed when the link to BlackMatter’s portal leaked on Twitter. It seems like many people hold ransomware gangs in less-than-high regard, and took the opportunity to inform BlackMatter of this fact, using that portal. In response, BlackMatter took down that portal site, cutting off Emsisoft’s line of information. Since then, the encryption vulnerability has been fixed, Emisoft can’t listen in on BlackMatter anymore, and they released the story to encourage BlackMatter victims to contact them. They also suggest that ransomware victims always contact law enforcement to report the incident, as there may be a decryptor that isn’t public yet. Continue reading “This Week In Security: The Battle Against Ransomware, Unicode, Discourse, And Shrootless” →