Normally, if you change a file’s extension in Windows, it doesn’t do anything positive. It just makes the file open in the wrong programs that can’t decode what’s inside. However, [PortalRunner] has crafted a file that can behave as six different filetypes, simply by swapping out the extension at the end of the filename.

The basic concept is simple enough. [PortalRunner] simply found a bunch of different file formats that could feasibly be crammed in together into a single file without corrupting each other or confusing software that loads these files.

It all comes down to how file formats work. File extensions are mostly meaningless to the content of a file—they’re just a shorthand guide so an operating system can figure out which program should load them. In fact, most files have headers inside that indicate to software what they are and how their content is formatted. For this reason, you can often rename a .PNG file to .JPEG and it will still load—because the operating system will still fire up an image viewer app, and that app will use headers to understand that it’s actually a PNG and not a JPEG at heart, and process it in the proper way.

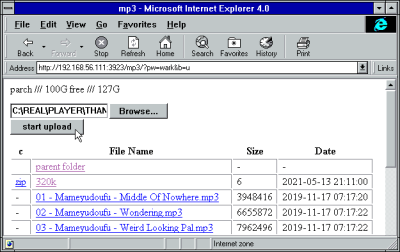

[PortalRunner] found a way to merge the headers of various formats, creating a file that could be many different types. The single file contains data for a PNG image, an MP4 video, a PDF document, a ZIP archive, a Powerpoint presentation, and an HTML webpage. The data chunks for each format are lumped into one big file, with the combined headers at the very top. The hijinx required to pull this off put some limitations on what the file can contain, and the files won’t work with all software… but it’s still one file that has six formats inside.

This doesn’t work for every format. You can’t really combine GIF or PNG for example, as each format requires a different initial set of characters that have to be at the very beginning of the file. Other formats aren’t so persnickety, though, and you can combine their headers in a way that mostly works if you do it just right.

If you love diving into the binary specifics of how file formats work, this is a great project to dive into. We’ve seen similarly mind-bending antics from [PortalRunner] before, like when they turned Portal 2 into a webserver. Video after the break.

Continue reading “One File, Six Formats: Just Change The Extension”