We have seen many scam USB chargers appear over the years, with a number of them being enthusiastically ripped apart and analyzed by fairly tame electrical engineers. Often these are obvious scams with clear fire risks, massively overstated claims and/or electrocution hazards. This is where the “600W” multi-port USB charger from AliExpress that [Denki Otaku] looked at is so fascinating, as despite only outputting 170 Watt before cutting out, it’s technically not lying in its marketing and generally well-engineered.

The trick being that the “600W” is effectively just the model name, even if you could mistake it for the summed up output power as listed on the ports. The claimed GaN components are also there, with all three claimed parts counted and present in the main power conversion stages, along with the expected efficiency gains.

While testing USB-PD voltages and current on the USB-C ports, the supported USB-PD EPR wattage and voltages significantly reduce when you start using ports, indicating that they’re clearly being shared, but this is all listed on the product page.

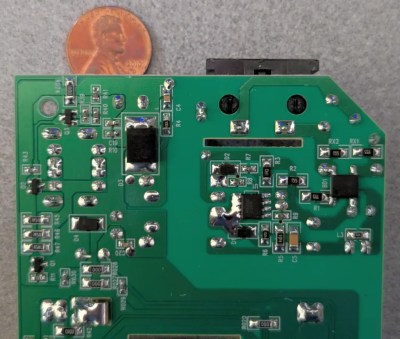

The main PCB of the unit generates the 28 VDC that’s also the maximum voltage that the USB-C ports can output, with lower voltages generated as needed. On the PCB with the USB ports we find the step-down converters for this, as well as the USB-PD and other USB charging control chips. With only a limited number of these to go around, the controller will change the current per port dynamically as the load increases, as you would expect.

Considering that this particular charger can be bought for around $30, is up-front about the limitations and uses GaN, while a genuine 300 Watt charger from a brand like Anker goes for $140+, it leads one to question the expectations of the buyer more than anything. While not an outright scam like those outrageous $20 ‘2 TB’ SSDs, it does seem to prey on people who have little technical understanding of what crazy amounts of cash you’d have to spend for a genuine 600 Watt GaN multi-port USB charger, never mind how big such a unit would be.

Continue reading “When USB Charger Marketing Claims Are Technically True”