Making stamps out of potatoes that have been cut in half is always a fun activity with the kids. But if you’ve got a 3D printer, you could really step up your printing game by building a mini relief printing press.

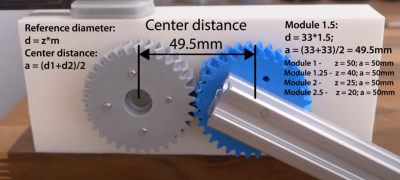

To create the gear bed/rack, [Kevr102] used a Fusion 360 add-in called GF Gear Generator. At first this was the most finicky part of the process, but then it was time to design the roller gears. However, [Kevr102] got through it with some clever thinking and a little bit of good, old-fashioned eyeballing.

Per [Kevr102], this press is aimed at the younger generation of printers in that the roller mechanism is spring-loaded to avoid pinched fingers. [Kevr102] 3D-printed some of the printing tablets, which is a cool idea. Unfortunately it doesn’t work that well for some styles of text, but most things came out looking great. You could always use a regular linocut linoleum tile, too.

This isn’t the first 3D-printed printing press to grace these pages. Here’s one that works like a giant rubber stamp.

durability and increase noise. On the other hand, helical gears have a more gradual engagement, resulting in reduced noise and smoother operation. This leads to an increased load-carrying capacity, thus improving durability and lifespan.

durability and increase noise. On the other hand, helical gears have a more gradual engagement, resulting in reduced noise and smoother operation. This leads to an increased load-carrying capacity, thus improving durability and lifespan.