Full disclosure: [Óscar] isn’t nine now, but he was in 1988 when he wrote LOCS, a drawing program in Z80 assembly modeled after Logo. You can see a demo of the system in the video below. You might wonder why you’d want to study a three-decade-old program written for a CPU by a nine-year-old almost five decades ago. Well, honestly, we aren’t sure either. But it did get us thinking.

Kids today are computer savvy and have hardware that would seem to be alien tech in 1988. How many of them could duplicate this feat? Now, how many could do it in assembly language?

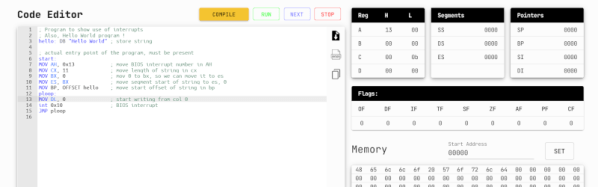

LOCS had a few simple commands and was sort of a stripped-down scripting language. The BORRA command clears the screen. TORTUGA centers the turtle. PT (pone tortuga) moves the turtle to any spot on the screen. Then SM, AM, DM, and IM move the turtle up, down, right, and left. Probably helps if you speak a little Spanish.

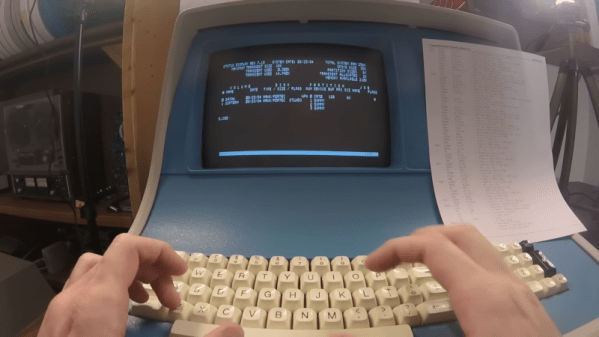

The program fits on three pages of handwritten code. When was the last time you wrote code on paper? [Óscar] revisits the program to run it on an MSX. The original program was under 500 bytes but adding the code for MSX balloons it to 589 bytes. Gotta love assembly language.

You could argue that LOCS isn’t a language because it doesn’t have variables, expressions, or looping. [Óscar] retorts that HTML doesn’t have those things either, and yet some call it a language. Honestly, if a 9-year-old can create this, we think they can call it anything they want to!

By 1990, he’d graduated to full-blown games. If turtle graphics are too abstract for you, try a Big Trak.