Building a computer on a breadboard is a seminal project for many builders, but it can become complicated quite quickly, not to mention that all the parts needed for a computer are being placed on a medium which often lends itself to loose wires and other hardware bugs. [3DSage] has a working breadboard computer that is as simple as it can possibly be, putting it together piece by piece to show exactly what’s needed to get a computer which can count, access memory, and even perform basic mathematical operations.

The first step for any computer is to build a clock, and in this case it’s being provided by a 555 timer which is configured to provide an adjustable time standard and which steps through the clock pulses when a button is pressed. The next piece is a four-bit counter and a memory chip, which lets the computer read and write data. A set of DIP switches allows a user to write data to memory, and by using the last three bits of the data as opcodes, the computer can reset, halt, and jump to various points in a simple program.

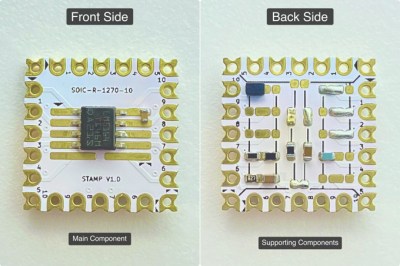

Although these three chips make it possible to perform basic programming, [3DSage] takes this a bit further in his video by demonstrating some other simple programs, such as one which can play music or behave as an alarm clock. He also shows how to use a fourth chip in the form of a binary adder to perform some basic math, and then packages it all into a retro-styled computer kit. Of course you can take these principles and build them out as far as they will go, like this full 8-bit computer built on a breadboard or even this breadboard computer that hosts a 486.