For anyone with even the slightest bit of engineering interest, wind turbines are hard to resist. Everything about them is just so awesome, in the literal sense of the word — the size of the blades, the height of the towers, the mechanical guts that keep them pointed into the wind. And as if one turbine isn’t enough, consider the engineering implications of planting a couple of hundred of these giants in a field and getting them to operate as a unit. Simply amazing.

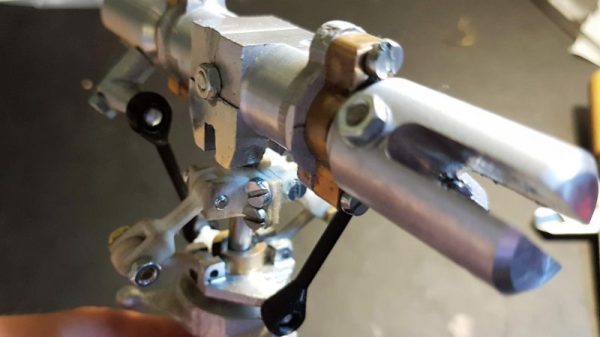

Unfortunately, the thing that makes wind turbines so cool — their enormity — can make them difficult to wrap your head around. To fix that, [3DprintedLife] built a working miniature wind turbine that goes a bit beyond most designs of a similar size. The big difference here is variable pitch blades, a feature the big turbines rely on to keep their output maximized over a broad range of wind conditions. The mechanism here is clever — the base of each blade rides in a bearing and has a small cap head screw that rides in a hole in a triangular swash block in the center of the hub. A small gear motor and lead screw move the block back and forth along the hub’s axis, which changes the collective pitch of the blades.

Other details of full-sized wind turbines are replicated here too, like the powered nacelle rotation and the full suite of wind speed and direction sensors. The generator is a NEMA 17 stepper; the output is a bit too anemic to actually power the turbine’s controller, but that could be fixed with gearing changes. Still, all the controls worked as planned, and there’s room for improvement, so we’ll score this a win overall.

Looking for a little more on full-size wind turbines? You’re in luck — our own [Bryan Cockfield] shared his insights into how wind farm engineers deal with ice and cold.

Continue reading “3D Printed Wind Turbine Has All The Features, Just Smaller”