At the level pursued by many Hackaday readers, the advent of affordable 3D printing has revolutionised prototyping, as long as the resolution of a desktop printer is adequate and the part can be made in a thermoplastic or resin, it can be in your hands without too long a wait. The same has happened at a much higher level, but for those with extremely deep pockets it extends into exotic high-performance materials which owners of a desktop FDM machine can only dream of.

NASA for example are reporting their new 3D printable nickel-cobalt-chromium alloy that can produce extra-durable laser-sintered metal parts that van withstand up to 2000 Fahrenheit, or 1033 Celcius for non-Americans. This has obvious applications for an organisation producing spacecraft, so naturally they are excited about it.

The alloy receives some of its properties because of its oxide-dispersion-strengthened composition, in which grains of metal oxide are dispersed among its structure. We’re not metallurgists here at Hackaday, but we understand that the inconsistencies in the layers of metal atoms caused by the oxides in the crystal structure of the alloy leads to a higher energy required for the structure to shear.

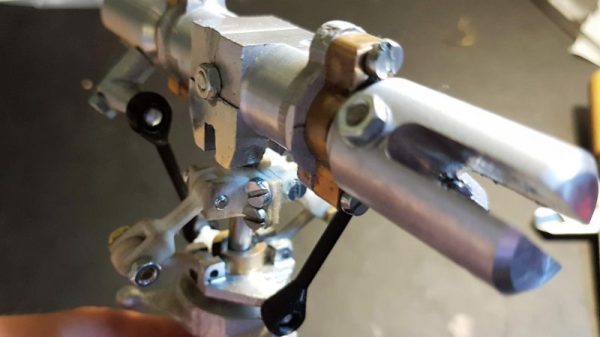

While these particular materials might never be affordable for us mere mortals to play with, NASA’s did previously look into how it could greatly reduce the cost of high-temperature 3D printing by modifying an existing open source machine.