A large part of fighting against the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is the practice of contact tracing, where the whereabouts of an infected person can be traced and anyone who has been in contact with that person over the past days tested for COVID-19. While smartphone apps have been a popular choice for this kind of tracing, they come with a range of limitations, which is what the TraceTogether hardware token seeks to circumvent. Now [Sean “Xobs” Cross] has taken a look at the hardware that will be inside the token once it launches.

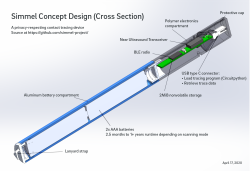

Recently, [Sean] along with [Andrew “bunnie” Huang] and a few others were asked by GovTech Singapore to review their TraceTogether hardware token proposal. At its core it’s similar to the Simmel contact tracing solution – on which both are also working – with contacts stored locally in the device, Bluetooth communication, and a runtime of a few months or longer on the non-rechargeable batteries.

The tracing protocol used is BlueTrace, which is an open application protocol aimed at digital contact tracing. It was developed by the Singaporean government, initially for use with their TraceTogether mobile app.

This smartphone app showed a number of issues. First is that Apple does not allow for iOS apps to use Bluetooth in the background, requiring the app to be active in the foreground to be useful. Apple has its own tracing protocol, but it does not cover the requirements for building a full contact graph, as [Andrew] covers in more detail. Finally, the app in general is not useful to those who do not have a recent (compatible) smartphone, or who do not have a smartphone at all.

A lot of the challenges in developing these devices lie in making them low-power, while still having the Bluetooth transceiver active often enough to be useful, as well as having enough space to store interactions and the temporary tokens that are used in the tracing protocol. As Simmel and the TraceTogether tokens become available over the coming months, it will be interesting to see how well these predictions worked out.