When Mary Wallace “Wally” Funk reached the boundary of space aboard the first crewed flight of Blue Origin’s New Shepard capsule earlier today, it marked the end of a journey she started 60 years ago. In 1961 she became the youngest member of what would later become known as the “Mercury 13”, a group of accomplished female aviators that volunteered to be put through the same physical and mental qualification tests that NASA’s Mercury astronauts went through. But the promising experiment was cut short by the space agency’s rigid requirements for potential astronauts, and what John Glenn referred to in his testimony to the Committee on Science and Astronautics as the “social order” of America at the time.

commercial space26 Articles

Virgin Galactic’s Long Road To Commercial Spaceflight

To hear founder Richard Branson tell it, the first operational flight of Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo has been 18 months out since at least 2008. But a series of delays, technical glitches, and several tragic accidents have continually pushed the date back to the point that many have wondered if it will ever happen at all. The company’s glacial pace has only been made more obvious when compared with their rivals in the commercial spaceflight field such as SpaceX and Blue Origin, which have made incredible leaps in bounds in the last decade.

But now, at long last, it seems like Branson’s suborbital spaceplane might finally start generating some income for the fledgling company. Their recent successful test flight, while technically the company’s third to reach space, represents an important milestone on the road to commercial service. Not only did it prove that changes made to Virgin Space Ship (VSS) Unity in response to issues identified during last year’s aborted flight were successful, but it was the first full duration mission to fly from Spaceport America, the company’s new operational base in New Mexico.

The data collected from this flight, which took pilots Frederick “CJ” Sturckow and Dave Mackay to an altitude of 89.23 kilometers (55.45 miles), will be thoroughly reviewed by the Federal Aviation Administration as part of the process to get the vehicle licensed for commercial service. The next flight will have four Virgin Galactic employees join the pilots, to test the craft’s performance when loaded with passengers. Finally, Branson himself will ride to the edge of space on Unity’s final test flight as a public demonstration of his faith in the vehicle.

If all goes according to plan, the whole process should be wrapped up before the end of the year. At that point, between the government contracts Virgin Galactic has secured for testing equipment and training astronauts in a weightless environment, and the backlog of more than 600 paying passengers, the company should be bringing in millions of dollars in revenue with each flight.

Continue reading “Virgin Galactic’s Long Road To Commercial Spaceflight”

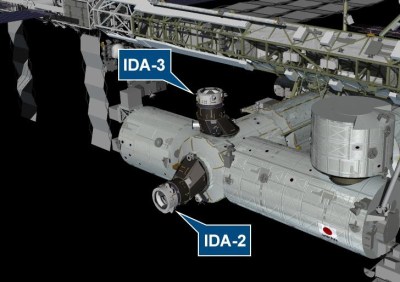

Crew Dragon’s Short Hop Begins The Era Of Valet Parking At The ISS

They weren’t scheduled to return to Earth until April 28th at the earliest, so why did NASA astronauts Michael Hopkins, Victor Glover, and Shannon Walker, along with Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) astronaut Soichi Noguchi, suit up and climb aboard the Crew Dragon Resilience on April 5th? Because a previously untested maneuver meant that after they closed the hatch between their spacecraft and the International Space Station, there was a chance they weren’t going to be coming back.

On paper, moving a capsule between docking ports seems simple enough. All Resilience had to do was undock from the International Docking Adapter 2 (IDA-2) located on the front of the Harmony module, itself attached to the Pressurized Mating Adapter 2 (PMA-2) that was once the orbital parking spot for the Space Shuttle, and move over to the PMA-3/IDA-3 on top of Harmony. It was a short trip through open space, and when the crew exited their craft and reentered the Station at the end of it, they’d only be a few meters from where they started out approximately 45 minutes prior.

The maneuver was designed to be performed autonomously, so technically the crew didn’t need to be on Resilience when it switched docking ports. But allowing the astronauts to stay aboard the station while their only ride home undocked and flew away without them was a risk NASA wasn’t willing to take.

The maneuver was designed to be performed autonomously, so technically the crew didn’t need to be on Resilience when it switched docking ports. But allowing the astronauts to stay aboard the station while their only ride home undocked and flew away without them was a risk NASA wasn’t willing to take.

What if the vehicle had some issue that prevented it from returning to the ISS? A relocation of this type had never been attempted by an American spacecraft before, much less a commercial one like the Crew Dragon. So while the chances of such a mishap were slim, the crew still treated this short flight as if it could be their last day in space. Should the need arise, all of the necessary checks and preparations had been made so that the vehicle could safely bring its occupants back to Earth.

Thankfully, that wasn’t necessary. The autonomous relocation of Crew Dragon Resilience went off without a hitch, and SpaceX got to add yet another “first” to their ever growing list of accomplishments in space. But this first relocation of an American spacecraft at the ISS certainly won’t be the last, as the comings and goings of commercial spacecraft will only get more complex in the future.

Continue reading “Crew Dragon’s Short Hop Begins The Era Of Valet Parking At The ISS”

Rocket Lab Plans Larger Neutron Rocket For 2024

When Rocket Lab launched their first Electron booster in 2017, it was unlike anything that had ever flown before. The small commercially developed rocket was the first to use fully 3D printed main engines, and instead of pumping its propellants with traditional turbines, the vehicle used electric motors that jettisoned their depleted battery packs overboard during ascent to reduce weight. It even looked different than its peers, as rather than a metal fuselage, the Electron was built from a lightweight carbon composite which gave it a distinctive black color scheme.

Packing so many revolutionary technical advancements into a single vehicle was a risk, but Rocket Lab founder Peter Beck believed a technical shakeup was the only way to get ahead in an increasingly competitive market. While that first launch in 2017 didn’t make it to orbit, the next year, Rocket Lab could boast three successful flights. By the end of 2020, a total of fifteen Electron rockets had completed their missions, carrying payloads from both commercial customers and government agencies such as NASA, the United States Air Force, and DARPA.

Rocket Lab’s gambit paid off, and the company has greatly outpaced competitors such as Virgin Orbit, Astra, and Relativity. In fact Electron is now the second most active orbital booster in the United States, behind SpaceX’s Falcon 9. Considering their explosive growth, it’s only natural they’d want to maintain that momentum going forward. But even still, the recent announcement that the company will be developing a far larger rocket they call Neutron to fly by 2024 took many in the industry by surprise; especially since Peter Beck himself had previously said they would never build it.

Continue reading “Rocket Lab Plans Larger Neutron Rocket For 2024”

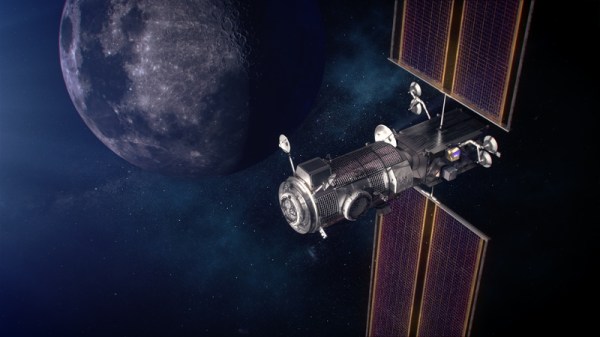

NASA Selects SpaceX To Launch Lunar Gateway

While not a Cabinet position, the NASA Administrator is nominated by the president of the United States and tasked with enacting their overall space policy. As such, a new occupant in the White House has historically resulted in a different long-term directive for the agency. Some presidents have wanted bold programs of exploration, while others have directed NASA to follow a more reserved and economical path, with the largest shifts traditionally happening when the administration changes hands between the parties.

So it’s no surprise that the fate of Artemis, a bold program initiated by the previous administration that aims to establish a sustainable human presence on the Moon, has been considered uncertain since the November election. But the recent announcement that SpaceX has been awarded a $331.8 million contract to launch the first two modules of the lunar Gateway station, an orbital outpost that will serve as a rallying point for astronauts coming and going to the Moon’s surface, should help quell some concerns. While the components still aren’t slated to fly until 2024 at the earliest, it’s a step in the right direction and strong indicator that the new administration plans on seeing Artemis through.

Continue reading “NASA Selects SpaceX To Launch Lunar Gateway”

Europa Decision Delivers Crushing Blow To NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS)

These days, NASA deciding to launch one of their future missions on a commercial rocket is hardly a surprise. After all, the agency is now willing to fly their astronauts on boosters and spacecraft built and operated by SpaceX. Increased competition has made getting to space cheaper and easier than ever before, so it’s only logical that NASA would reap the benefits of a market they helped create.

So the recent announcement that NASA’s Europa Clipper mission will officially fly on a commercial launch vehicle might seem like more of the same. But this isn’t just any mission. It’s a flagship interplanetary probe designed to study and map Jupiter’s moon Europa in unprecedented detail, and will serve as a pathfinder for a future mission that will actually touch down on the moon’s frigid surface. Due to the extreme distance from Earth and the intense radiation of the Jovian system, it’s considered one of the most ambitious missions NASA has ever attempted.

With no margin for error and a total cost of more than $4 billion, the fact that NASA trusts a commercially operated booster to carry this exceptionally valuable payload is significant in itself. But perhaps even more importantly, up until now, Europa Clipper was mandated by Congress to fly on NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS). This was at least partly due to the incredible power of the SLS, which would have put the Clipper on the fastest route towards Jupiter. But more pragmatically, it was also seen as a way to ensure that work on the Shuttle-derived super heavy-lift rocket would continue at a swift enough pace to be ready for the mission’s 2024 launch window.

With no margin for error and a total cost of more than $4 billion, the fact that NASA trusts a commercially operated booster to carry this exceptionally valuable payload is significant in itself. But perhaps even more importantly, up until now, Europa Clipper was mandated by Congress to fly on NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS). This was at least partly due to the incredible power of the SLS, which would have put the Clipper on the fastest route towards Jupiter. But more pragmatically, it was also seen as a way to ensure that work on the Shuttle-derived super heavy-lift rocket would continue at a swift enough pace to be ready for the mission’s 2024 launch window.

But with that deadline fast approaching, and engineers feeling the pressure to put the final touches on the spacecraft before it gets mated to the launch vehicle, NASA appealed to Congress for the flexibility to fly Europa Clipper on a commercial rocket. The agency’s official line is that they can’t spare an SLS launch for the Europa mission while simultaneously supporting the Artemis Moon program, but by allowing the Clipper to fly on another rocket in the 2021 Consolidated Appropriations Act, Congress effectively removed one of the only justifications that still existed for the troubled Space Launch System.

Continue reading “Europa Decision Delivers Crushing Blow To NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS)”

Failed Test Could Further Delay NASA’s Troubled SLS Rocket

The January 16th “Green Run” test of NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) was intended to be the final milestone before the super heavy-lift booster would be moved to Cape Canaveral ahead of its inaugural Artemis I mission in November 2021. The full duration static fire test was designed to simulate a typical launch, with the rocket’s main engines burning for approximately eight minutes at maximum power. But despite a thunderous start start, the vehicle’s onboard systems triggered an automatic abort after just 67 seconds; making it the latest in a long line of disappointments surrounding the controversial booster.

When it was proposed in 2011, the SLS seemed so simple. Rather than spending the time and money required to develop a completely new rocket, the super heavy-lift booster would be based on lightly modified versions of Space Shuttle components. All engineers had to do was attach four of the Orbiter’s RS-25 engines to the bottom of an enlarged External Tank and strap on a pair of similarly elongated Solid Rocket Boosters. In place of the complex winged Orbiter, crew and cargo would ride atop the rocket using an upper stage and capsule not unlike what was used in the Apollo program.

There’s very little that could be called “easy” when it comes to spaceflight, but the SLS was certainly designed to take the path of least resistance. By using flight-proven components assembled in existing production facilities, NASA estimated that the first SLS could be ready for a test flight in 2016.

If everything went according to schedule, the agency expected it would be ready to send astronauts beyond low Earth orbit by the early 2020s. Just in time to meet the aspirational goals laid out by President Obama in a 2010 speech at Kennedy Space Center, including the crewed exploitation of a nearby asteroid by 2025 and a potential mission to Mars in the 2030s.

But of course, none of that ever happened. By the time SLS was expected to make its first flight in 2016, with nearly $10 billion already spent on the program, only a few structural test articles had actually been assembled. Each year NASA pushed back the date for the booster’s first shakedown flight, as the project sailed past deadlines in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020. After the recent engine test ended before engineers were able to collect the data necessary to ensure the vehicle could safely perform a full-duration burn, outgoing NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said it was too early to tell if the booster would still fly this year.

What went wrong? As commercial entities like SpaceX and Blue Origin move in leaps and bounds, NASA seems stuck in the past. How did such a comparatively simple project get so far behind schedule and over budget?

Continue reading “Failed Test Could Further Delay NASA’s Troubled SLS Rocket”