[Alex Le Roux] want to 3D print houses. Rather than all the trouble we go through now, the contractor would make a foundation, set-up the 3D printer, feed it concrete, and go to lunch.

It’s by no means the first concrete printer we’ve covered, but the progress he’s made is really interesting. It also doesn’t hurt that he’s claimed to make the first livable structure in the United States. We’re not qualified to verify that statement, maybe a reader can help out, but that’s pretty cool!

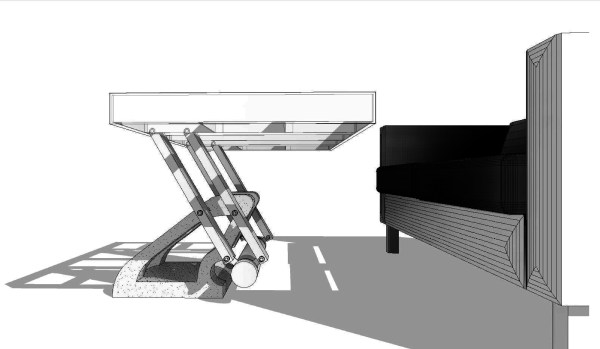

The printer is a very scaled gantry system. To avoid having an extremely heavy frame, the eventual design assumes that the concrete will be pumped up to the extruder; for now he is just shoveling it into a funnel as the printer needs it. The extruder appears to be auger based, pushing concrete out of a nozzle. The gantry contains the X and Z. It rides on rails pinned to the ground which function as the Y. This is a good solution that will jive well with most of the skills that construction workers already have.

Having a look inside the controls box we can see that it’s a RAMPS board with the step and direction outputs fed into larger stepper drivers, the laptop is even running pronterface. It seems like he is generating his STLs with Sketch-Up.

[Alex] is working on version three of his printer. He’s also looking for people who would like a small house printed. We assume it’s pretty hard to test the printer after you’ve filled your yard with tiny houses. If you’d like one get in touch with him via the email on his page. His next goal is to print a fully up to code house in Michigan. We’ll certainly be following [Alex]’s tumblr to see what kind of progress he makes next!