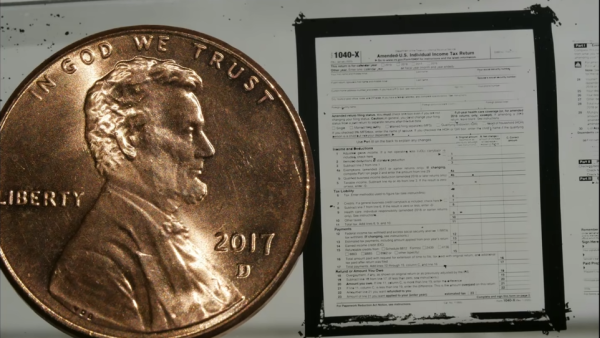

In the same way that a doctor often needs to take a non-destructive look inside a patient to diagnose a problem, those who seek to reverse engineer electronic systems can greatly benefit from the power of X-ray vision. The trouble is that X-ray cabinets designed for electronics are hideously expensive, even on the secondary market. Unless, of course, their sensors are kaput, in which case they’re not of much use. Or are they?

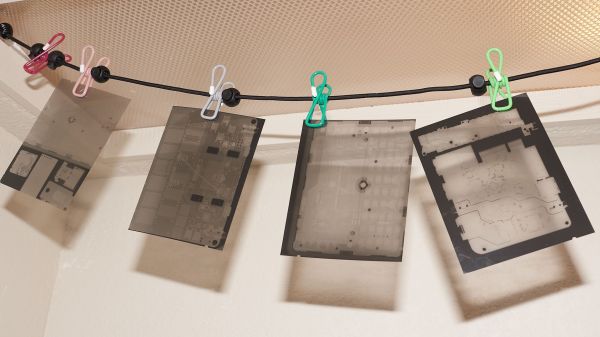

[Aleksandar Nikolic] and [Travis Goodspeed] strongly disagree, to the point that they dedicated a lot of work documenting how they capture X-ray images on plain old analog film. Of course, this is nothing new — [Wilhelm Konrad Roentgen] showed that photographic emulsions are sensitive to “X-light” all the way back in the 1890s, and film was the de facto image sensor for radiography up until the turn of this century. But CMOS sensors have muscled their way into film’s turf, to the point where traditional silver nitrate emulsions and wet processing of radiographic films, clinical and otherwise, are nearly things of the past. Continue reading “Reviving A Sensorless X-Ray Cabinet With Analog Film”