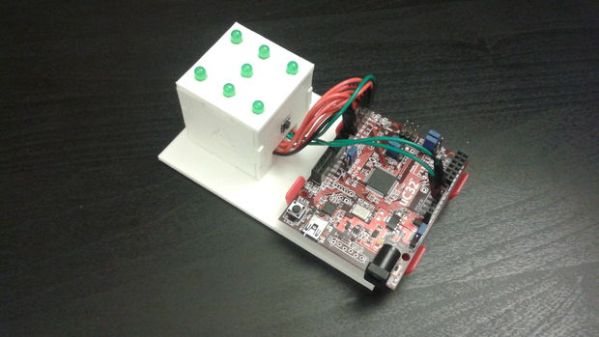

There’s no shortage of projects that replace your regular board game dice with an electronic version of them, bringing digital features into the real world. [Jean] however goes the other way around and brings the real world into the digital one with his Bluetooth equipped electronic dice.

These dice are built around a Simblee module that houses the Bluetooth LE stack and antenna along with an ARM Cortex-M0 on a single chip. Adding an accelerometer for side detection and a bunch of LEDs to indicate the detected side, [Jean] put it all on a flex PCB wrapped around the battery, and into a 3D printed case that is just slightly bigger than your standard die.

While they’ll work as simple LED lighted replacement for your regular dice as-is, their biggest value is obviously the added Bluetooth functionality. In his project introduction video placed after the break, [Jean] shows a proof-of-concept game of Yahtzee displaying the thrown dice values on his mobile phone. Taking it further, he also demonstrates scenarios to map special purposes and custom behavior to selected dice and talks about his additional ideas for the future.

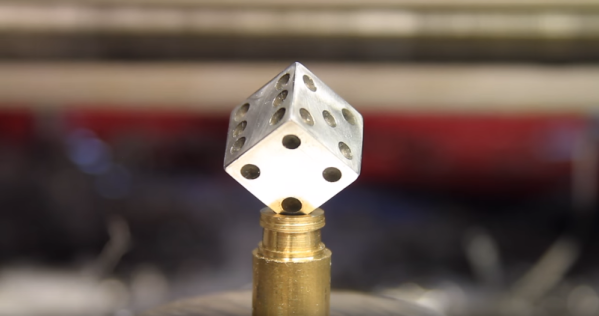

After seeing the inside of the die, it seems evident that getting a Bluetooth powered D20 will unfortunately remain a dream for another while — unless, of course, you take this giant one as inspiration for the dimensions.

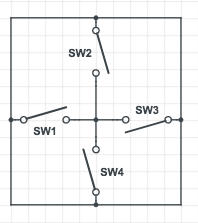

[Vejdemo-Johansson] figured a circle of 4 tilt sensors mounted on the one and twenty face would be enough to detect critical rolls. If any of the switches were tilted beyond 30 degrees, the switch would close. He mounted eight ball-tilt switches and glued in the LEDs. A hackerspace friend also helped him put together an astable multivibrator to generate the pulses for non-critical rolls.

[Vejdemo-Johansson] figured a circle of 4 tilt sensors mounted on the one and twenty face would be enough to detect critical rolls. If any of the switches were tilted beyond 30 degrees, the switch would close. He mounted eight ball-tilt switches and glued in the LEDs. A hackerspace friend also helped him put together an astable multivibrator to generate the pulses for non-critical rolls.