Like many classic board games, Ludo offers its players numerous opportunities to inflict frustration on other players. Despite this, [Viktor Takacs] apparently enjoys it, which motivated him to build a thoroughly modernized, LED-based, WiFi-enabled game board for it (GitHub repository).

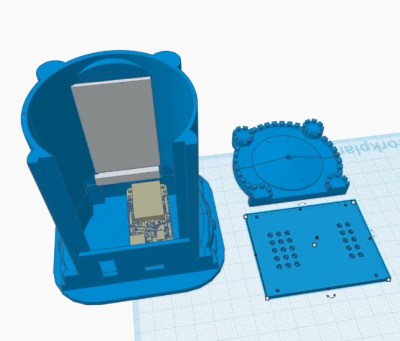

The new game board is built inside a stylish 3D-printed enclosure with a thin white front face, under which the 115 LEDs sit. Seven LEDs in the center represent a die, and the rest mark out the track around the board and each user’s home row. Up to six people can play on the board, and different colors of the LEDs along the track represent their tokens’ positions. To prevent light leaks, a black plastic barrier surrounds each LED. Each player has one button to control their pieces, with a combination of long and short presses serving to select one of the possible actions.

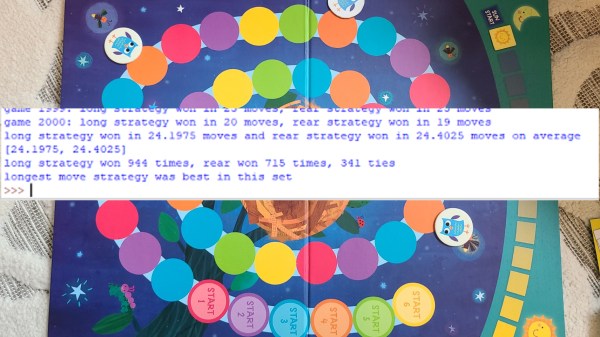

The electronics themselves are mounted on seven circuit boards, which were divided into sections to reduce their size and therefore their manufacturing cost. For component placement reasons, [Viktor] used a barrel connector instead of USB, but for more general compatibility also created an adapter from USB-C to a barrel plug. The board is controlled by an ESP32-S3, which hosts a server that can be used to set game rules, configure player colors, save and load games, and view statistics for the game (who rolled the most sixes, who sent other players home most often, etc.).

If you prefer your games a bit more complex, we’ve also seen electronics added to Settlers of Catan. On a rather larger scale, there is also this LED-based board game which invites humans onto the board itself. Continue reading “Adding Electronics To A Classic Game”