Because people are generally idiots when it comes to choosing passwords — including people who should know better — Google created Google Authenticator. It’s two-factor verification for all your Google logins based on a shared secret key. It’s awesome, and everyone should use it.

Actually typing in that code from a phone app is rather annoying, and [Alistair] has a better solution: an Authenticator USB Key. Instead of opening up the Authenticator app every time he needs an Authenticator code, this USB key will send the code to Google with the press of a single button.

The algorithm behind Google Authenticator is well documented and actually very simple; it’s just a hash of the current number of 30-second periods since the Unix epoch and an 80-bit secret key. With knowledge of the secret key, you can generate Authenticator codes until the end of time. It’s been done with an Arduino before, but [Alistair]’s project makes this an incredibly convenient way to input the codes without touching the keyboard.

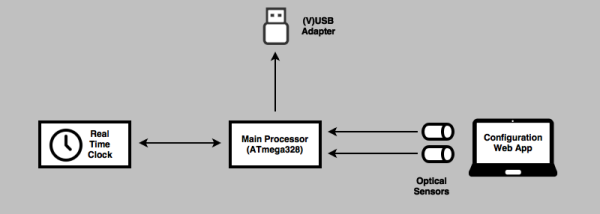

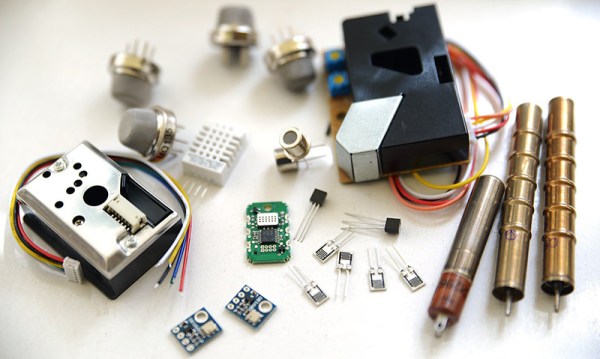

The current plan is to use an ATMega328, a real-time clock, and VUSB for generating the Authenticator code and sending it to a computer. Getting the secret key on the device sounds tricky, but [Alistair] has a trick up his sleeve for that: he’s going to use optical sensors and a flashing graphic on a web page to send the key to the device. It’s a bit of a clunky solution, but considering the secret key only needs to be programmed once, it’s not necessarily a bad solution.

With a small button plugged into a USB hub, [Alistair] has the perfect device for anyone annoyed at the prospect at opening up the Authenticator app every few days. It’s not a replacement for the app, it just makes everything easier.