There are a lot of environmental monitors in the running for this year’s Hackaday Prize. Whether they’re soil moisture sensors for gardens or ultraviolet sensors for the beach, the entrants for The Hackaday Prize seem to grasp the inevitable truth that you need information about the environment before doing anything about the environment.

But what about sharing that information? Wouldn’t it be handy if there were an online repository where you could look up environmental conditions of any location on the planet? That’s where [radu.motisan]’s Portable Environmental Monitor comes in. It’s a small, pocketable device that measures just about everything and uploads that data to the Internet.

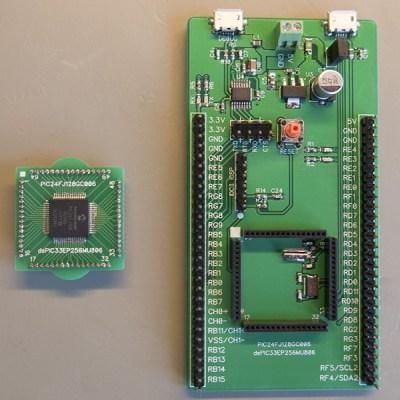

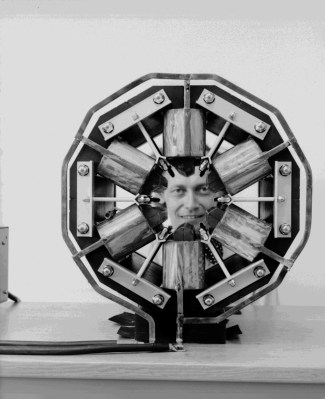

This project is a continuation of [radu]’s entry for The Hackaday Prize last year, the Global Radiation Monitoring Network. This was more than just a Geiger tube connected to the Internet; [radu] has a global network of Geiger counters displaying counts per minute on a nifty live map.

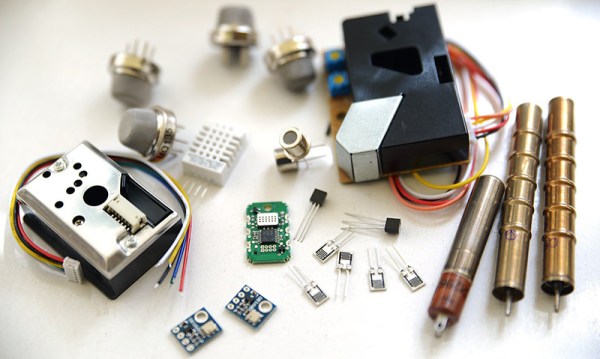

[radu]’s latest project expands on the capabilities of the Global Radiation Monitoring Network with more sensors and portability. Inside the Environmental Monitor are enough sensors to look at Alpha, Beta and Gamma radiation, dust and toxic gas, and other types of pollution. With the addition of an ESP8266 WiFi module, this portable device can upload sensor readings to the Internet, greatly expanding [radu]’s uRADMonitor network.