Well, that was “fun”. Last week, we wrote a newsletter post about the state of Hackaday’s comments. We get good ones and bad ones, and almost all the time, we leave you all up to your own devices. But every once in a while, it’s good to remind people to be nice to our fellow hackers who get featured here, because after all they are the people doing the work that gives us something to read and write about. The whole point of the comment section is for you all to help them, or other Hackaday readers who want to follow in their footsteps.

Someone decided to let loose a comment-reporting attack. It works like this: you hit the “report comment” button on a given comment multiple times from multiple different IP addresses, and our system sends the comments back to moderation until a human editor can re-approve them. Given the context of an article about moderation, most everyone whose comment disappeared thought that we were behind it. When more than 300 comments were suddenly sitting in the moderation queue, our weekend editors figured something was up and started un-flagging comments as fast as they could. Order was eventually restored, but it was ugly for a while.

We’ve had these attacks before, but probably only a handful of times over the last ten years, and there’s basically nothing we can do to prevent them that won’t also prevent you all from flagging honestly abusive or spammy comments. (For which, thanks! It helps keep Hackaday’s comments clean.) Why doesn’t it happen all the time? Most of you all are just good people. Thanks for that, too!

But despite the interruption, we got a good discussion started about how to make a comment section thrive. A valid critique of our current system that was particularly evident during the hack is that the reported comment mechanism is entirely opaque. A “your comment is being moderated” placeholder would be a lot nicer than simply having the comment disappear. We’ll have to look into that.

But despite the interruption, we got a good discussion started about how to make a comment section thrive. A valid critique of our current system that was particularly evident during the hack is that the reported comment mechanism is entirely opaque. A “your comment is being moderated” placeholder would be a lot nicer than simply having the comment disappear. We’ll have to look into that.

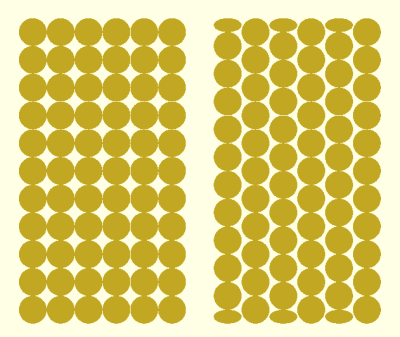

You were basically divided down the middle about whether an upvote/downvote system like on Reddit or Slashdot would serve us well. Those tend to push more constructive comments up to the top, but they also create a popularity contest that can become its own mini-game, and that’s not necessarily always a good thing. Everyone seemed pretty convinced that our continuing to allow anonymous comments is the right choice, and we think it is simply because it removes a registration burden when someone new wants to write something insightful.

What else? If you could re-design the Hackaday comment section from scratch, what would you do? Or better yet, do you have any examples of similar (tech) communities that are particularly well run? How do they do it?

We spend our time either writing and searching for cool hacks, or moderating, and you can guess which we’d rather. At the end of the day, our comments are made up of Hackaday readers. So thanks to all of you who have, over the last week, thought twice and kept it nice.