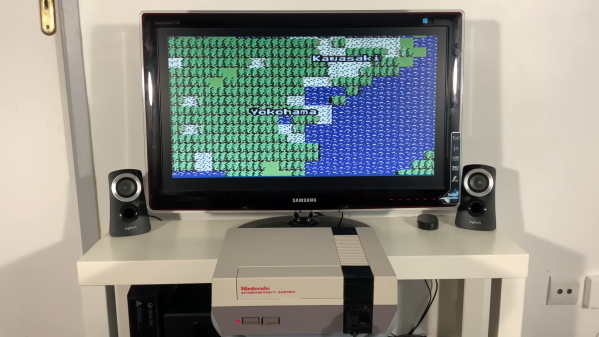

Many holiday recipes and console hacks share a common theme: cramming a thing inside another thing. Whether it’s turducken or a Nintendo DS inside a Gameboy, the result is always unexpected. The chassis for this mod is a humble Gameboy color with a Gameboy SP screen tackled on the top to serve as the secondary display. Unfortunately, this mod lost touch screen functionality, limiting some of the games you can play.

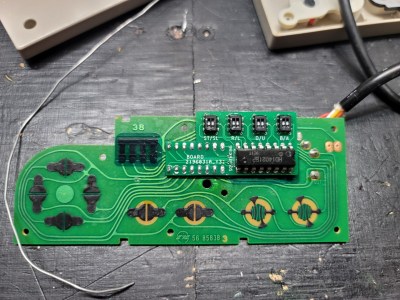

[TheRetroFuture] received the custom handheld from [GameboyCustom], which was somewhat damaged in shipping. The original screw mounts had to be removed and the case glued back together to fit the DS motherboard. So for [TheRetroFuture] to get inside to start troubleshooting involved a razor blade and patience. Testing various points and swapping components got [TheRetroFuture] closer to the root problems. The fix ended up being a few wires that came loose during shipping. Finally, after reseating a display connection and some careful soldering, it booted and started playing games.

Overall, it’s pretty impressive to see Mario Kart DS running on both screens on the tiny handheld. But you might be asking, why? Why shove one handheld inside another handheld? Sometimes it’s to gain new functionality like this Raspberry Pi inside a PSP body. Sometimes, it’s just because we can. Video after the break.