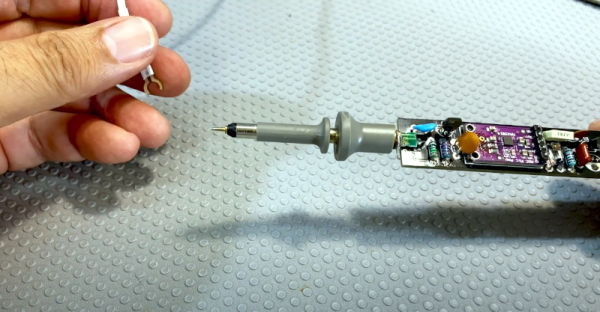

Repairing radios was easier when radios were simple. There were typically two strategies. You could use a signal tracer (an amplifier) to listen at the volume control. If you heard something, the problem was after the volume control. If you didn’t, then the problem was something earlier in the signal path. Then you find a point halfway again, and probe again. No signal tracer? You can also inject a signal. If you hear it, the problem is before the volume. If not, it is after. But where do you get the signal to inject? [Learn Electronics Repair] sets out to make a small one in a recent video you can see below.

Both signal tracers and injectors were once ubiquitous pieces of equipment when better options were expensive. However, these days, you can substitute an oscilloscope for a signal tracer and a signal generator for an injector. Still, it is a fun project, and a small dedicated instrument can be handy if you repair a lot of radios.

The origin of this project was from an earlier signal injector design and a bet with a friend about making a small version. They are both working on their designs and want people to submit their own designs for a little ad hoc contest.

We always preferred a signal tracer since it is more passive. Those were typically just audio amplifiers with an optional diode in the input to demodulate RF. A computer amplified speaker and a diode can do the job, as can an LM386. Or, you can build something complex, if you prefer.