Learning something on YouTube seems kind of modern. But if you are watching a 1957 instructional film about slide rules, it also seems old-fashioned. But Encyclopædia Britannica has a complete 30-minute training film, which, what it lacks in glitz, it makes up for in mathematical rigor.

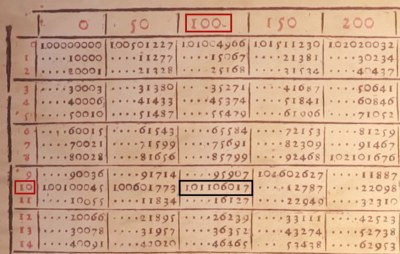

We appreciated that it started out talking about numbers and significant figures instead of jumping right into the slide rule. One thing about the slide rule is that you have to sort of understand roughly what the answer is. So, on a rule, 2×3, 20×30, 20×3, and 0.2×300 are all the same operation.

You don’t actually get to the slide rule part for about seven minutes, but it is a good idea to watch the introductory part. The lecturer, [Dr. Havery E. White] shows a fifty-cent plastic rule and some larger ones, including a classroom demonstration model. We were a bit surprised that the prestigious Britannica wouldn’t have a bit better production values, but it is clear. Perhaps we are just spoiled by modern productions.

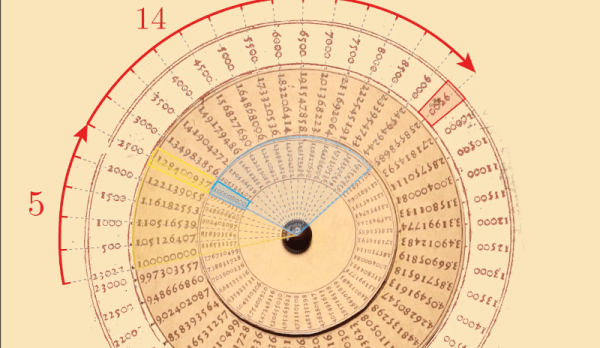

We love our slide rules. Maybe we are ready for the collapse of civilization and the need for advanced math with no computers. If you prefer reading something more modern, try this post. Our favorites, though, are the cylindrical ones that work the same, but have more digits.

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: Learning The Slide Rule The New Old Fashioned Way”