Underwater Remote Operated Vehicles, or ROVs as they’re typically known, generally operate by tether. This is due to the poor propagation of radio waves underwater. [Simon] wanted to build such a drone, but elected to go for an alternative design with less strings attached, so to speak. Thus far, there have been challenges along the way. (Video, embedded below.)

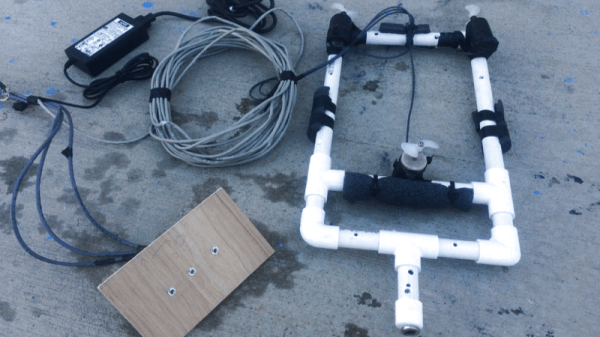

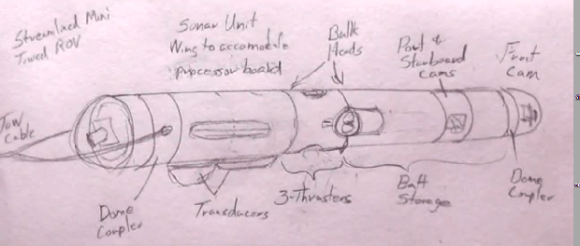

The underwater drone uses a 3D printed chassis, replete with googly eyes that go a long way to anthropomorphizing the build. Four motors are used for control, with two for thrust in the horizontal plane and two mounted in the vertical plane for attitude control. This allows the drone to be set up at neutral buoyancy, and moved through the water column with thrust rather than complicated ballast mechanisms. The build aims to eschew tethers, instead using a shorter cable to link to a floating unit which uses radio to communicate with the operator on the shore.

The major struggle facing the build has been sealing the chassis against water ingress. This is where the layered nature of 3D printing is a drawback. Even with several treatments of paint and sealant, [Simon] has been unable to stop water getting inside the drone. Further problems concern the excess amount of ballast required to counteract the drone’s natural buoyancy due to displacement.

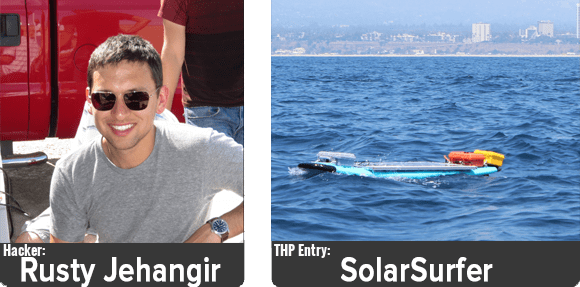

Regardless of the struggles, we look forward to seeing the next revision rectify some of the shortcomings of the current build. We’re sure [Simon’s] experience building an electric surfboard will come in handy. Video after the break.