When thinking about forests being endangered by human activity, most people would immediately think of the rainforest. Below the ocean surface, there’s another type of forest is in danger: the kelp forests off the coast of northern California. Warming sea water has triggered an explosion in the population of purple sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) which devour kelp at an alarming rate. It’s estimated that 90% of kelp forests have been lost to the urchins along a 350 km stretch of coastline.

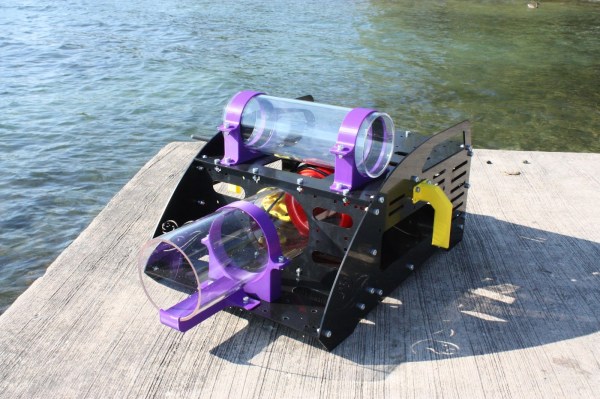

The fix is as simple as getting rid of the urchins, but collecting the millions of spiny creatures manually isn’t realistic. Luckily, [RobotGrrl] designed just the tool for this task: Otter Force One, an autonomous underwater robot that can gather the aquatic interlopers and put them in a bag for removal. The device is still under development, but progress so far has been promising. The basic idea is to identify an urchin using machine vision, then dislodge it with a water jet, and finally to use a suction pump to pull it inside the machine and store it in a bag.

A prototype made from 3D printed components is currently being used to test the idea. Its motors are driven by an ESP32 with a motor controller, with the system powered by a set of beefy lithium batteries. Tests with plastic urchin models confirm that the suction mechanism works, though the water jet and machine vision systems still need to be tested. But even without these in place the Otter Force One can still be used by human divers to improve their urchin-gathering efficiency.

A prototype made from 3D printed components is currently being used to test the idea. Its motors are driven by an ESP32 with a motor controller, with the system powered by a set of beefy lithium batteries. Tests with plastic urchin models confirm that the suction mechanism works, though the water jet and machine vision systems still need to be tested. But even without these in place the Otter Force One can still be used by human divers to improve their urchin-gathering efficiency.

We’ll definitely keep an eye on this project, and hopefully see it evolve into a fully-automated urchin hunter. Underwater pest-control robots are not completely new: we already saw a laser-powered delouser for use on salmon farms. There are also robotic starfish and octopuses.