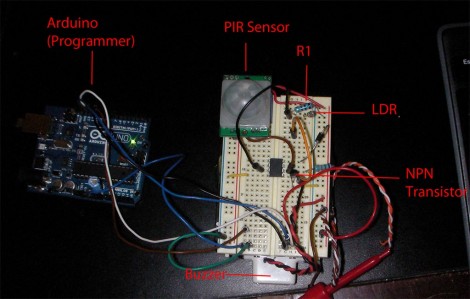

[Brad] was asked by his Sister to design a motion-based alarm that would help her catch her son sneaking out of the house at night. Obviously this didn’t need to be a long-term installation so he decided to throw something together that is only active at night and can be battery-powered. What he came up with is a light-sensitive motion sensor that uses very little power.

He knew that an Arduino would be overkill, and decided to try his hand at using the Arduino to develop code for an ATtiny85. It has an external interrupt pin connected to the output of the PIR module, which triggers action when motion is detected. The first thing it does is to check the photoresistor via the ADC. If light levels are low enough, the buzzer will be sounded. [Brad] measured the current consumption of his circuit and was not happy to find it draws about 2.5 mA at idle. He spent some time teaching himself about the sleep functions of the AVR chips and was able reduce that to about 500-600 uA when in sleep mode. Now all he has to do is find a nice place behind the house to mount the alarm and there’ll be no more sneaking around at night.

If you’re trying to keep a tight leash on your own kids you could always make them punch the time clock.