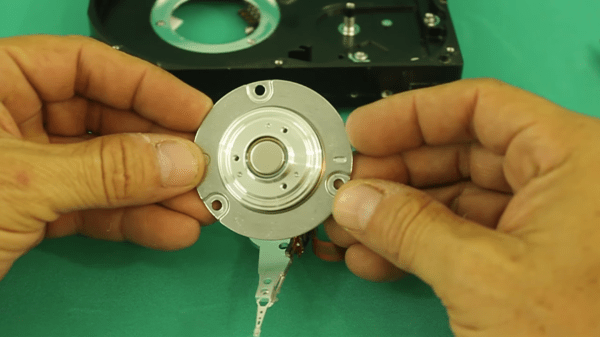

A rite of passage for a young electronics enthusiast used to be collecting an array of surplus boards from whatever could be found, and using them as sources of parts to desolder. It was possible with a bit of work and searching to build all manner of electronic projects without spending much at all. Many hardware hackers know their way around consumer electronics from the decade before their teenage years as a result. Secondhand components can still be used, but the type of components to be found has changed, as well as those needed. [ElectricMonkeyBrain] takes a look, and asks “What should you desolder?”.

As a general rule, he lands on the premise that it’s worth hanging on to the expensive stuff rather than the cheap stuff. Large capacitors, power semiconductors, and inductors aren’t cheap at all, and in the case of the inductors they can yield both ferrite parts and enameled wire for rewinding to suit. We’re surprised that he advocates holding on to electrolytic capacitors as a kit of many values is now pretty cheap, but it’s understandable that if you lack the part and it’s there on a motherboard in front of you, it’s worth desoldering. Finally, he discusses cases, something we’ve been tempted by a few times more than we’d like to mention.

In a world of easy online ordering, it’s useful to be reminded that sometimes there’s still space for salvaged parts, after all, no delivery service is as quick as reaching under your bench for an old ATX power supply to raid. As always though, don’t amass too much of it.