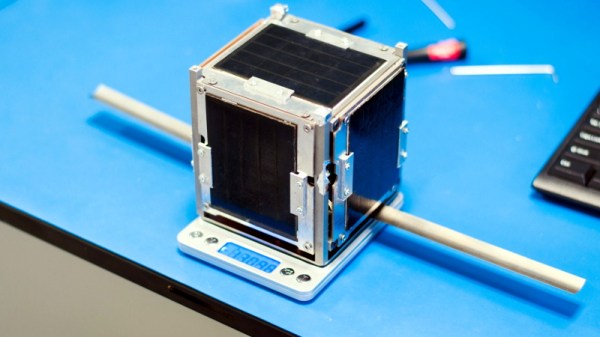

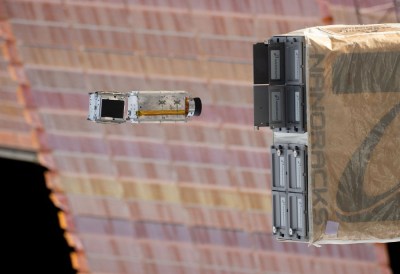

On the 3rd of June 2019, a 1U CubeSat developed by students of the AGH University of Science and Technology in Kraków was released from the International Space Station. Within a few hours it was clear something was wrong, and by July 30th, the satellite was barely functional. A number of problems contributed to the gradual degradation of the KRAKsat spacecraft, which the team has thoroughly documented in a recently released paper.

We all know, at least in a general sense, that building and operating a spacecraft is an exceptionally difficult task on a technical level. But reading through the 20-pages of “KRAKsat Lessons Learned” gives you practical examples of just how many things can go wrong.

It all started with a steadily decreasing battery voltage. The voltage was dropping slowly enough that the team knew the solar panels were doing something, but unfortunately the KRAKsat didn’t have a way of reporting their output. This made it difficult to diagnose the energy deficit, but the team believes the issue may have been that the tumbling of the spacecraft meant the panels weren’t exposed to the amount of direct sunlight they had anticipated.

This slow energy drain continued until the voltage dropped to the point that the power supply shut down, and that’s were things really started going south. Once the satellite shut down the batteries were able to start charging back up, which normally would have been a good thing. But unfortunately the KRAKsat had no mechanism to remain powered down once the voltage climbed back above the shutoff threshold. This caused the satellite to enter into and loop where it would reboot itself as many as 150 times per orbit (approximately 90 minutes).

The paper then goes into a laundry list of other problems that contributed to KRAKsat’s failure. For example, the satellite had redundant radios onboard, but the software on them wasn’t identical. When they needed to switch over to the secondary radio, they found that a glitch in its software meant it was unable to access some portions of the onboard flash storage. The team also identified the lack of a filesystem on the flash storage as another stumbling block; having to pull things out using a pointer and the specific memory address was a cumbersome and time consuming task made all the more difficult by the spacecraft’s deteriorating condition.

Of course, building a satellite that was able to operate for a couple weeks is still an impressive achievement for a student team. As we’ve seen recently, even the pros can run into some serious technical issues once the spacecraft leaves the lab and is operating on its own.

[Thanks to ppkt for the tip.]