Although Nintendo is mostly famous for making great games, they also have an infamous reputation for being highly litigious not only for reasonable qualms like outright piracy of their games, but additionally for more gray areas like homebrew development on their platforms or posting gameplay videos online. With that sort of reputation it’s not surprising that they don’t release open-source drivers for their platforms, especially those like the Wii U with unique controllers that are difficult to emulate. This Wii U gamepad emulator seeks to bridge that gap.

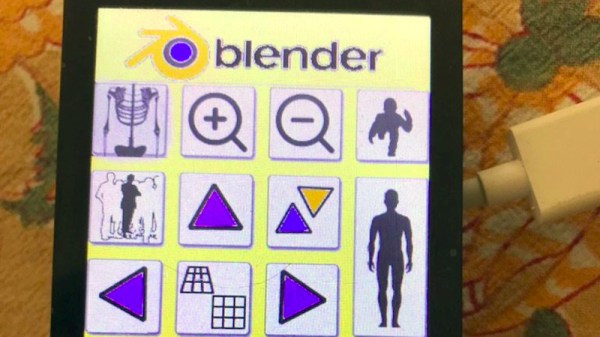

The major issue with the Wii U compared to other Nintendo platforms like the SNES or GameCube is that the controller looks like a standalone console and behaves similarly as well, with its own built-in screen. Buying replacement controllers for this unusual device isn’t straightforward either; outside of Japan Nintendo did not offer an easy path for consumers to buy controllers. This software suite, called Vanilla, aims to allow other non-Nintendo hardware to bridge this gap, bringing in support for things like the Steam Deck, the Nintendo Switch, various Linux devices, or Android smartphones which all have the touch screens required for Wii U controllers. The only other hardware requirement is that the device must support 802.11n 5 GHz Wi-Fi.

Although the Wii U was somewhat of a flop commercially, it seems to be experiencing a bit of a resurgence among collectors, retro gaming enthusiasts, and homebrew gaming developers as well. Many games were incredibly well made and are still experiencing continued life on the Switch, and plenty of gamers are looking for the original experience on the Wii U instead. If you’ve somehow found yourself in the opposite position of owning of a Wii U controller but not the console, though, you can still get all the Wii U functionality back with this console modification.

Thanks to [Kat] for the tip!