Judging by the over-representation of the term “AI” in our news feeds these days, we’re clearly in the exponential phase of the artificial intelligence hype cycle, and very nearly at the dreaded “Peak of Inflated Expectations.” It seems like there’s nothing that AI can’t do, and nowhere that its principles can’t be applied to virtuous — and profitable — effect.

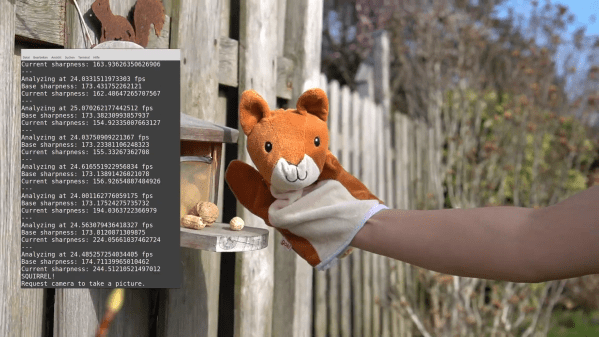

We don’t deny that AI has massive potential, but we strongly suspect that there will soon come a day when eyes will roll and stomachs will turn at yet another AI application that could have been addressed with something easier. An example of the simpler approach can be seen in this non-AI wildlife photo trap, cobbled together by [Sebastian] to capture pictures of some camera-shy squirrels. Rather than train an AI with gigabytes of squirrel images, he instead relies on his old Sony Alpha camera, which has a built-in WiFi. A Python script connects to the camera, which is trained on a feeder box and set to a very narrow depth of field. That makes a good percentage of the scene out of focus until a squirrel or other animal comes along looking for treats. The script detects the increased area of the scene that is now in-focus with a Laplace operator in OpenCV, and triggers the camera shutter. [Sebastian] ended up with some wonderful shots of the shy squirrels using this scheme; the video below describes the setup in more detail.

It’s not the first time we’ve seen Laplace transforms used to gauge image sharpness, of course, but we really like the approach [Sebastian] took here for its simplicity. The squirrels are cute too.

Continue reading “An AI-Free Way To Catch Wildlife On Camera”