So it seems that Microsoft has a patent in process for a folding mouse. It looks a whole lot like their Arc mouse, which is quite thin and already goes from curved to flat. But that’s apparently not good enough for Microsoft, who says mice in general are bulky and cumbersome to travel with. On the bright side, they do acknowledge the total lack of ergonomics in those tiny travel mice.

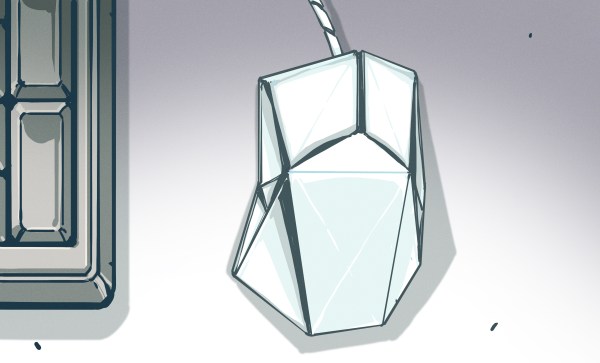

Microsoft filed this patent in March of 2021 and it was published in early November. The patent describes the use of an expandable shell on the top with these kerf cuts in the long sides like those used to bend wood — this is where the flexibility comes in. The patent also mentions a motion tracker, haptic feedback, and a wireless charging coil. Now remember, there’s no guarantee of this ever actually happening, and there was no comment from Microsoft about whether it will become a real rodent someday.

And now, the rant. Microsoft considers this mouse, which again is essentially an updated Arc that folds in half, to be ergonomic. Full disclosure: I’ve never used an Arc mouse. But I respectfully disagree with this assessment and believe that people should not prioritize portability when it comes to peripherals, especially those that are so small to begin with. Like, what’s the use? And by the way, isn’t anyone this concerned with portability just using the touch pad or steering stick on their laptop anyway?

Continue reading “Microsoft’s Minimal Mouse May Maximize Masochism”