Although these days it would seem that everyone and their pets are running 3D printers to churn out all the models and gadgets that their hearts desire, a more traditional approach to creating physical 3D models is in the form of paper models. These use designs printed on paper sheets that are cut out and assembled using basic glue, but creating these designs is much easier these days, as [Arvin Poddar] demonstrates in a recent article.

The cool part about making these paper models is that you create them from any regular 3D mesh, with any STL or similar file from your favorite 3D printer model site like Printables or Thingiverse being fair game, though [Arvin] notes that reducing mesh faces can be trickier than modelling from scratch. In this case he created the SR-71 model from scratch in Blender, featuring 732 triangles. What the right number of faces is depends on the target paper type and your assembly skills.

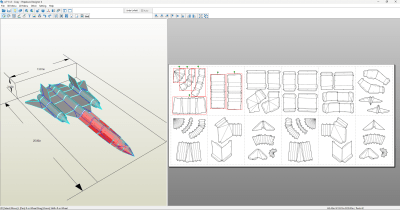

Following mesh modelling step is mesh unfolding into a 2D shape, which is where you have a few software options, like the paid-for-but-full-featured Pepakura Designer demonstrated, as well as the ‘Paper Model’ exporter for Blender.

Beyond the software used to create the SR-71 model in the article, the only tools you really need are a color printer, paper, scissor,s and suitable glue. Of course you are always free to use fancier tools than these to print and cut, but the bar here is pretty low for the assembly. Although making functional parts isn’t the goal here, there is a lot to be said for paper models for pure display pieces and to get children interested in 3D modelling.