Last week, we ran a post about a slightly controversial video that claimed that a particular 3D-printing slicing strategy was tied up by a patent troll. We’re absolutely not lawyers here at Hackaday, but we’ve been in the amateur 3D printing revolution since the very beginning, and surprisingly patents have played a role all along.

Modern fused-deposition modelling (FDM) 3D printing began with Stratasys’ patent US5121329A, “Apparatus and method for creating three-dimensional objects”, and the machines they manufactured and sold based on the technology. Go read the patent, it’s an absolute beauty and has 44 different claims that cover just about everything in FDM printing. This was the watershed invention, and today, everything claimed in the patent is free.

Stratasys’ patent on the fundamental FDM method kept anyone else from commercializing it until the patent expired in 2009. Not coincidentally, the first available home-gamer 3D printer, the Makerbot Cupcake, also went on sale in 2009.

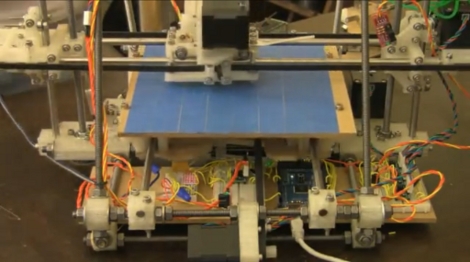

The Stratasys machines were also one of the big inspirations for Adrian Bowyer to start the RepRap project, the open-source movement that basically lead to us all having cheap and cheerful 3D printers today, and he didn’t let the patent stop him from innovating before it lapsed. Indeed, the documentation for the RepRap Darwin dates back to 2007. Zach [Hoeken] Smith delivered our hackerspace the acrylic parts to make one just around that time, and we had it running a year or two before the Cupcake came out of the company that he, Bre, and Adam shortly thereafter founded.

The story of hackers and 3D printers is longer than the commercial version of the same story would imply, and a lot of important innovations have come out of our community since then too. For instance, have a look at Stratasys’ patent on heated bed technology. At first read, it seems to cover removable heated beds, but have a look at the cutout at the end of claim 1: “wherein the polymer coating is not a polymer tape”. This cutout is presumably in response to the at-the-time common practice of buying Kapton, PEI, or PET tape and applying that to removable heated bed surfaces. I know I was doing that in 2012, because I read about it on IRC or something, long before the Stratasys patent was filed in 2014. They could only get a patent for sprayed-on coatings.

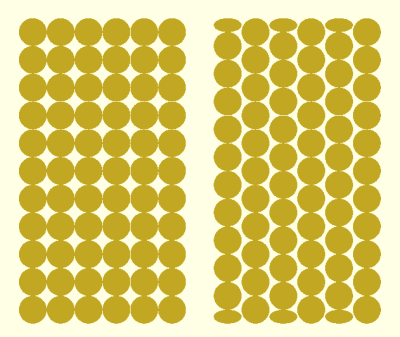

As [Helge] points out, it’s also easily verifiable that the current patent on “brick layers” that we’re worrying about, filed in 2020, comes later than this feature request to Prusa Slicer that covers essentially the same thing in 2019. We assume that the patent examiner simply missed that obvious prior art – they are human after all. But I certainly wouldn’t hesitate to implement this feature given the documented timing.

As [Helge] points out, it’s also easily verifiable that the current patent on “brick layers” that we’re worrying about, filed in 2020, comes later than this feature request to Prusa Slicer that covers essentially the same thing in 2019. We assume that the patent examiner simply missed that obvious prior art – they are human after all. But I certainly wouldn’t hesitate to implement this feature given the documented timing.

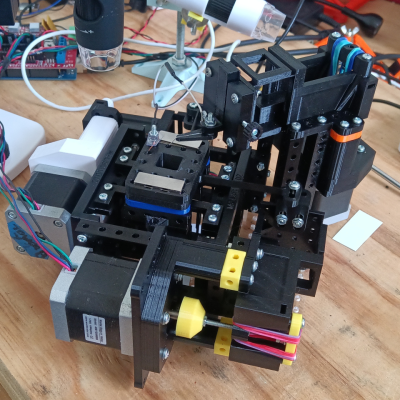

I would even be so bold as to say that most of the post-2010 innovation in 3D printing has been made by hobbyists. While the RepRap movement was certainly inspired by Stratasys’ invention in the beginning, our community is where the innovation is happening now, and maybe even more starkly on the software side of things than the hardware. Either way, as long as you’re just doing it for fun, let the suits worry about the patents. Hackers gotta hack.