Eagle 9 is out. Autodesk is really ramping up the updates to Eagle, so much so it’s becoming annoying. What are the cool bits this time? Busses have been improved, which is great because I’ve rarely seen anyone use busses in Eagle. There’s a new pin breakout thingy that automagically puts green lines on your pins. The smash command has been overhauled and now moving part names and values is somewhat automatic. While these sound like small updates, Autodesk is doing a lot of work here that should have been done a decade ago. It’s great.

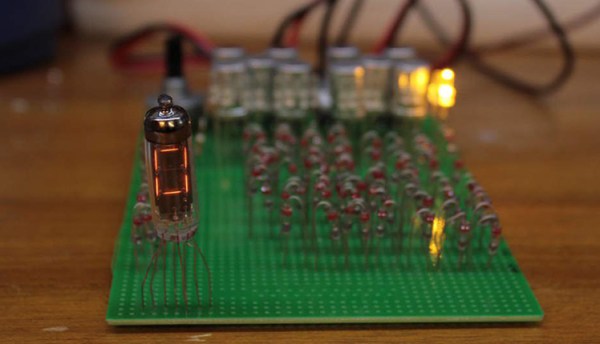

Crypto! Bitcoin is climbing up to $9,000 again, so everyone is all-in on their crypto holdings. Here’s an Arduino bitcoin miner. Stats of note: 150 hashes/second for the assembly version, and at this rate you would need 10 billion AVRs to mine a dollar a day. This array of Arduinos would need 2 Gigawatts, and you would be running a loss of about $10 Million per day (minus that one dollar you made).

Are you going to be at Hamvention? Hamvention is the largest amateur radio meetup in the Americas, and this year is going to be no different. Unfortunately, I’ll be dodging cupcake cars that weekend, but there is something of note: a ‘major broadcaster’ is looking for vendors for a ‘vintage tech’ television series. This looks like a Canadian documentary, which adds a little bit of respectability to this bit of reality television (no, really, the film board of Canada is great). They’re looking for weird or wacky pieces of tech, and items that look unique, strange, or spark curiosity. Set your expectations low for this documentary, though; I think we’re all several orders of magnitude more nerd than what would be interesting to a production assistant. ‘Yeah, before there were pushbutton phones, they all had dials… No, they were all attached to the wall…”

The new hotness on Sparkfun is a blinky badge. What we have here is a PCB, coin cell holder, color changing LED, and a pin clasp. It’s really not that different from the Tindie Blinky LED Badge. There is, however, one remarkable difference: the PCB is multicolored. The flowing unicorn locks are brilliant shades of green, blue, yellow, pink, purple, and red. How did they do it? We know full-color PCBs are possible, but this doesn’t look like it’s using a UV printer. Pad printing is another option, but it doesn’t look like that, either. I have no idea how the unicorn is this colorful. Thoughts?

Defcon is canceled, but there’s still a call for demo labs. They’re looking for hackers to show off what they’ve been working on, and to coax attendees into giving feedback on their projects.