Do you know core memory? Our prehistoric predecessors would store data in the magnetic fields of ferrite rings, reading out the ones and zeroes by setting the magnetic field and detecting if a small current is induced in a sense wire, indicating that the bit flipped, or not detecting the current, in which case it didn’t. Core memory is non-volatile, rad hard, and involved a tremendous amount of wire weaving to fabricate. And it’s pretty cool.

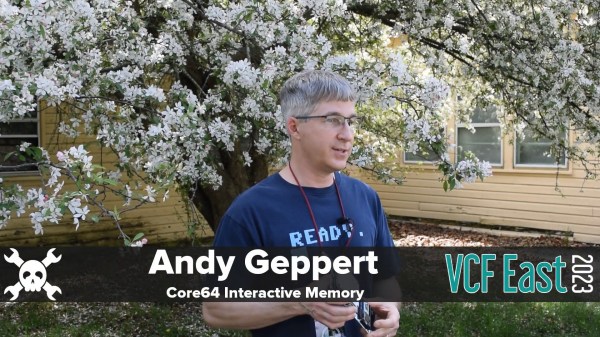

[Andy Geppert] wants to get you hands-on with this anachronistic memory, and builds kits to demo how it works. [Tom Nardi] and [Bil Herd] caught up with him at the Vintage Computer Festival East last weekend, and got him to demo his Core64 project for them. (Video, embedded below.)

The design of Core64 displays its state in lights at all times. And this means that you can write to it using either the onboard Pi Pico, for a blinky light show, or with a magnetic stylus, setting each bit’s magnetic state by hand. This turns it into a magnetic memory tablet and is a sweet demonstration of the principles that make it all work. Or, if you pulse the lines at just the right frequency, you can make the cores spin!

Watch [Andy] explaining it in our interview here, and stay tuned for more coming from VCF East 2023 soon.

Continue reading “VCF East 2023: Andy Geppert Talks Core Memory”