One of the features of the Raspberry Pi Zero is that it arrives with no GPIO header pins installed. The missing pins reduce the price of the little computer, as well as its shipping volume. A task facing most new Pi Zero owners has therefore been to solder a set of pins into the holes, and indeed many suppliers will sell you the pins alongside your new Zero.

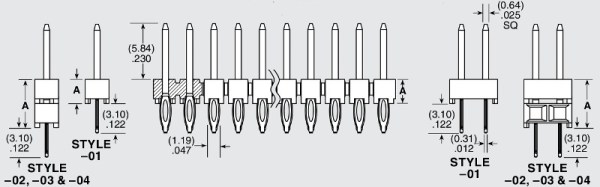

The British Pi accessories supplier Pimoroni think they may have a solution to this problem, with a set of solderless pins that the user is expected to fit by tapping both pins and Pi with a hammer. Each pin is designed to deform under pressure, and grip the through-plated walls of the hole in the PCB. In reality they are push-fit pins designed to be fitted with a press or a special tool, but since the average Zero buyer will have neither they supply a small laser-cut jig and give instructions to tap carefully with a pin hammer or similar. They have a demonstration as part of their regular Bilge Tank podcast, which we’ve included below the break.

Pins like these can be quite reliable when installed with the proper tools. They are often used in military and aerospace systems. In this case though, we expect that a chorus of you will be limbering up to comment that it would be far better to solder the connector, and we can’t help agreeing with you. Of course this product isn’t really marketed at Hackaday readers. Instead, the target market of a board like the Zero are children. For them soldering may well be a step too far. We can’t help wondering though whether hammer installation will deliver a reliable enough contact, and whether we’ll see a horde of youngsters whose Pi HATs don’t work due to dodgy connectors. Aside from the ones who’ve broken their Zeros with hammering that was a bit enthusiastic, that is.