Once upon a time, the poor humans of the past had to lug around suitcases and trunks with their own arms. Then, some genius figured out that you could just put wheels on and make everyone’s life a million times easier. Now, what if you didn’t even have push, because your luggage could just follow you instead? Well, students [Yuqiang Ge] and [Yiyang Zhao] have figured out a proof of concept for how that could work.

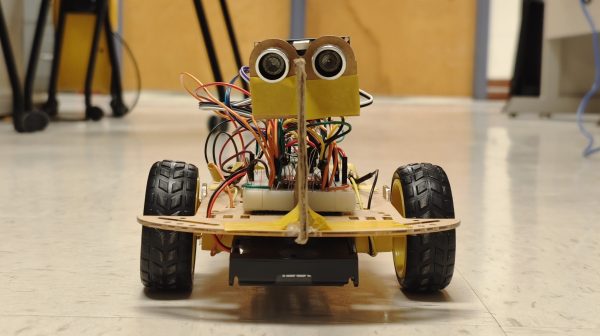

Their build is a small robotic platform that they assembled for their ECE5730 final project. The tiny wheeled robot is programmed to rotate on the spot until its infrared sensors pick up a signal. In turn, the user is intended to carry an infared beacon for it to lock onto. A pair of sensors are used on the robot platform, separated by a board to serve as a blind. The robot determines the relative signal strength from each sensor, and uses that to vary PWM signals to the two DC drive motors to steer the robot platform to seek and follow the infrared beacon.

It’s a neat idea, and looks to work pretty well in a university corridor. It even has an ultrasonic range sensor to (ideally) stop when it gets too close to the user. Whether it would survive the tumult of a crowded airport is another thing entirely, but that’s what the engineering process is about. Indeed, the very concept has been commercialized already!

Following-robots are a common student project, and one well worth exploring if you’re new to the robotic field.

Continue reading “Infrared Following Robot Built As Proof-of-Concept For Autonomous Luggage”