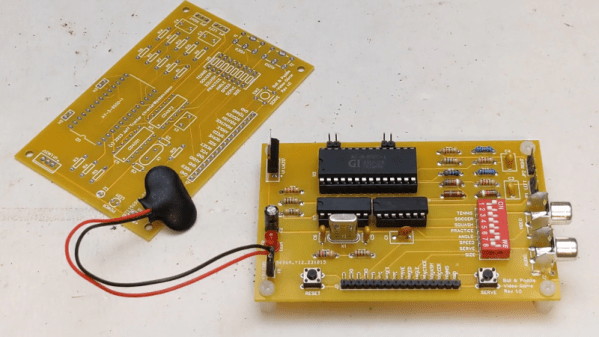

There are many venerable soundchips in the chiptune pantheon, of which the AY-3-8910 is perhaps one of the lesser known. Having not served on active duty for Nintendo or Commodore it’s somewhat unloved in the USA, but it made its name in a variety of arcade and pinball machines and has quite a European following due to its appearance in machines bearing the Amstrad and Sinclair names. [TheSpodShed] decided to whip up a USB MIDI interface for the chip, with the help of the Arduino Pro Micro.

The Arduino Pro Micro is a Sparkfun creation, using the ATmega32U4 microcontroller. Its USB MIDI functionality makes it a perfect candidate for such a build, and it also packs enough digital IO to run the AY-3-8910, with 13 lines required to get things going. [TheSpodShed] whipped up the project on protoboard, with only a few passives needed along with the sound chip and Arduino.

The Arduino code was written with an eye to making the most of the chip’s limited polyphony. The synth prioritises the most recent received notes, while also aiming to keep the highest and lowest of the currently requested notes still playing where possible. This gives the synth the best chance of keeping the expected bass and melody intact when playing a wide variety of MIDI content.

It’s a tidy build, and one that shows some love for a soundchip some have forgotten. Of course, it’s not the only option – we’ve also seen the SAM2695 and YM2612 given the same treatment. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Chiptunes Via USB MIDI With The AY-3-8910”